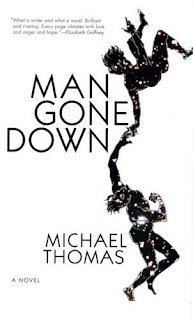

Man Gone Down

Once again this year I am endeavoring to read the ten books selected by the New York Times Book Review as the best of the year, and I start with Man Gone Down, a novel by Michael Thomas, and despite it being a debut from a small offshoot of Grove/Atlantic, it's easy to see why this book made the list. Michael Thomas can write. The book makes frequent mention of music, and the prose is very similar to music, whether it be jazz or the blues are old-fashioned rock and roll.

Once again this year I am endeavoring to read the ten books selected by the New York Times Book Review as the best of the year, and I start with Man Gone Down, a novel by Michael Thomas, and despite it being a debut from a small offshoot of Grove/Atlantic, it's easy to see why this book made the list. Michael Thomas can write. The book makes frequent mention of music, and the prose is very similar to music, whether it be jazz or the blues are old-fashioned rock and roll.The structure of the book is reminiscent of Richard Ford's novels about Frank Bascombe: a few days in the life of a typical American trying to deal with life's shit. But Thomas' unnamed narrator is world's apart from Ford's upper-middle class white guy. The narrator of this book is of mixed-race, though he identifies as black (he is also part Native-American and Irish, and describes what must have been an amusing trip to Dingle to try to find his roots). The man in question has a white wife and three young children, who have gone up to his native Boston to visit her family. He is left behind in Brooklyn, where he stays with an old friend, and must accomplish a series of things over four days: find a new apartment, come up with the tuition for his kids' private school, and try to keep his sanity.

Of course during these four days Thomas flashes back to the man's upbringing--his dissolute father, his mercurial mother, his friendships with schoolmates (one went insane, another perished in the World Trade Center) and just what it means to a black man in today's America. The character is a very intelligent one, who was a doctoral student in literature (his unfinished dissertation was on T.S. Eliot, who's quotations serve as chapter epigraphs) but at times he can be strangely inarticulate when it comes to speaking to people. He is also a musician (there's a great scene where he goes to an open-mike night) and a construction worker, taking day labor jobs. It is at one of these that a foreman calls him a "big nig" and Thomas' character doesn't take kindly to it.

There are many dazzlingly good passages, such as describing what it's like to drive his friend's Italian sports car down Manhattan's streets, jogging across the Brooklyn Bridge, giving his mother's ashes a viking funeral in the East River, and the penultimate scene, a golf game in a swanky country club with some white players. It is here, though, that I must mention the one thing I had trouble with the book, and that is Thomas' tendency to noodle with the language. Like a jazz musician, Thomas goes on riffs that occasionally pull away from the story and lead the reader (at least me) into confusion. During the golf game, while looking for an errant ball in the woods, Thomas' character has some sort of epiphany to an event in his past. I reread the passage three times and I still am not quite sure what's going on.

Nevertheless, even when I was a bit confused I enjoyed being in the thrall of Thomas' gift for language. This is a fine novel.

Comments

Post a Comment