The Third Man

This month at New York City's Film Forum there is a huge series called "Brit Noir," a retrospective of British films, mostly from the post-war period, that feature the seamier side of life. There are a total of 44 films being screened, and I would love to see every one of them. In one of my alternative lives, the one where I'm an independent man of means who lives in a fab Greenwich Village apartment and dates intellectual European girls who wear a lot of black and look like Audrey Hepburn, I would see each and every one. Instead I'll have to settle for renting the films that are available on DVD and writing about them here.

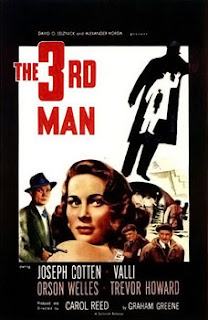

Of the 44 films I've only seen two previously. One of them is Night and the City, and the other is The Third Man, which opens the Film Forum series. I hadn't seen The Third Man in quite a while, though, so I purchased the Criterion Collection's DVD version and spent an enjoyable Sunday afternoon watching the film and the many extras.

The Third Man, which was named in a poll as the best British film of all time, is described as a "non-auteur film." This is because the idea germinated from the writer, Graham Greene, who was sent to Vienna by the producer Alexander Korda and asked to come up with a script. Greene had the kernel of an idea about a man who comes to a city to visit a friend, but hears that he is dead. Later, he is shocked when he sees the man alive. Greene researched Vienna, and learned about the ubiquitous black market, specifically the horrific practice of stealing penicillin and then diluting it for sale, which wreaked medical havoc on children and others.

The film was directed by Carol Reed, who has a somewhat unsung film legacy. He is certainly best known for The Third Man among the cognoscenti, but earned an Oscar for the lavish musical Oliver! Now I happen to think Oliver! is a terrific film, but that view is not universal, especially among those who feel that Reed's work in the forties and fifties is largely forgotten.

The Third Man, like Casablanca, is called a happy accident, as many things fell into place (hence the "non-auteur" tag). Consider the music, which is one of the aspects that it's best known for. Reed was in a wine bar in Vienna when he heard a man playing a strange instrument that he later learned was a zither. Reed got the bright idea to use it for the film, jettisoning a score played by the London Symphony Orchestra and using nothing but the zither playing of Anton Karas. The main theme would become a smash hit, making Karas a millionaire.

Then there's the cast. Originally it was conceived for Cary Grant as Holly Martins and Noel Coward as Harry Lime. This would have made the film much more British in tone, as the roles ended up going to Americans: Joseph Cotten and Orson Welles. It was Welles who would provide the film with a speech that would give The Third Man it's most lasting legacy.

The story concerns Cotten as Martins, a hack writer of pulp Westerns who arrives in post-war Vienna, which is reeling from the bombings and shortages of every kind. The city is divided into zones controlled by the Allies: Britain, France, Russia and the U.S. Martins has been promised a job by his old school chum, Lime, but shortly after arriving he learns that Lime is dead, and arrives at the cemetery just in time for his friend's funeral. There he meets a British military policeman, Trevor Howard, who tells Martins that Lime was a ruthless racketeer. Martins doesn't believe him, and begins to dig into the circumstances of Lime's death. When he gets conflicting witness reports involving a third man at the scene, he gets very suspicious, and teams up with Lime's girl, played by Alida Valli, to get to the bottom of things.

The film has the essential form of classic noir, with the amateur sleuth, the mysterious beauty, and several suspicious characters (a Baron who carries around a miniature Pinscher, a pinch-faced doctor, and a jocular Romanian). Greene, who despised much of American culture, scores several points by making his leading man a bumbler. In one of Cotten's early scenes he is seen walking under a ladder, and Howard describes him as "born to be murdered." He haplessly tries to seduce Valli, and gets bitten on the hand by a parrot. Sam Spade he's not.

In contrast, Harry Lime is viciously competent (yes, I am revealing Harry Lime is alive, it's not a well-kept secret among film buffs). Welles was wooed to play the part, though the American producer David O. Selznick objected, saying Welles was box office poison. He was convinced to play the part by Reed, who told him that his part was small but that he would steal the picture. In many ways Welles involvement in the film was like Marlon Brando's in Apocalypse Now--he earned a truckload of money for a few days work and exhibited diva-like behavior (he refused to film the climactic scene in Vienna's sewer, necessitating it be rebuilt in England's Shepperton Studios). The difference is that Welles elevated The Third Man to classic status while Brando almost sunk Apocalypse Now.

Harry Lime was said to be modeled after Kim Philby, a British double-agent, whom Greene remained friendly with even after Philby was disgraced. Indeed, Lime, with Welles as his voice, has a somewhat British demeanor, and is clearly Martins' better. The first appearance of Welles, hiding in a doorway, a cat at his feet, with a light exposing his smirking face, is one of the most striking in film history. The conversation that Welles and Cotton share on a Ferris wheel at the end of the picture is one of the most famous. In some respects it is to film what Hamlet's soliloquy is to drama, posing the moral question that hung in the air following the atrocities of World War II--how much is a human life worth? Welles asks Cotten to look down at the people below and wonders, "Would you really feel any pity if one of those dots stopped moving forever? If I offered you twenty thousand pounds for every dot that stopped, would you really, old man, tell me to keep my money, or would you calculate how many dots you could afford to spare?"

Of course Cotten is appalled, but doesn't have the words to express a counter-argument. Welles then improvises the film's most famous passage: "Like the fella says, in Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love - they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock." Because Welles wrote this bit, it is erroneously thought that he wrote all of his part, or even directed his scenes or the entire film, and in some interviews he didn't deny it (later in life he did). He was good-humored enough to relate that the Swiss pointed out to him that they have never manufactured cuckoo clocks.

Welles did later give Carol Reed all the credit, and a lot of credit is due him. Greene's script is magnificent, but Reed gave the film a look that has entranced audiences for sixty years. For one thing it is one of the best examples of a film that makes a city a character. They filmed this thing on the streets of Vienna, with all the Old World charm and rubble intact. Reed utilized the narrow passageways brilliantly, using light and shadow to an astonishing effect (credit here also to Robert Krasker, who won an Oscar for cinematography) and used an old noir trick of wetting the streets before shooting, making the cobblestones glisten. No matter how many times I see the film, I can't help but go slack-jawed at certain moments, such as when the old balloon salesman enters the square, or the way the shadow of a small boy makes him look like a giant, or the breath-taking final chase sequence in the sewer. To make the film even more expressionistic, the scenes are frequently filmed at an askew angle, which annoyed some critics but will remind others of the shots of the villain's lair in the old Batman TV series.

Then there's the very ending, a long shot of Valli walking toward the camera out of a cemetery, passing Cotten as he stands to the side, a perfect summation of the film. Ironically it wasn't the ending Greene wrote--he crafted a happy ending, with Cotten and Valli going off arm in arm. Reed argued against it, and Greene later fessed up that Reed was right.

Comments

Post a Comment