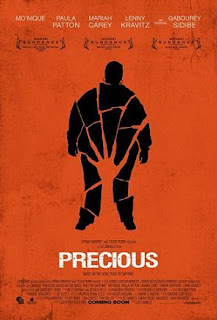

Precious

Precious has engendered a lot of punditry, both by film critics as well as those called upon to express opinions on all manner of social and cultural facets of American life. As such, it has been both wildly over-praised and unfairly vilified. I would never pretend to know how it fits in with the black experience, and frankly that doesn’t concern me. What interests me is was it a worthwhile experience watching it in a movie theater. For the most part, yes.

It is instructive that Oprah Winfrey signed on as an executive producer and endorsed it on her TV show. Oprah is the queen of daytime talk shows, and she is also the queen of good-intentioned, middlebrow entertainment, which is essentially what Precious is–an earnest tale of moral uplift with a sympathetic protagonist. At certain moments it is brilliantly moving, especially when focused on the two main performers, and at other times it wallows in a kind of self-satisfied Afterschool Specialness.

The story concerns the title character, an obese African American girl in Harlem in 1987. Played by Gabourey Sidibe, she would seem to have no hope. She is illiterate, although somehow gets good grades in school (albeit she is 16 and still in junior high). She is pregnant with her second child, both the result of rape by her father. Her daughter has Downs Syndrome, and is cruelly nicknamed “Mongo.” Her mother, scarily portrayed by Mo’Nique, is a lazy monster, telling Precious she is worthless, stupid and unloved, and there is nothing in the girl’s life to indicate otherwise.

Her school principal gets her transferred to an alternative school, where she meets a teacher, played by Paula Patton, who is like someone out of a fairy tale. Not only is she beautiful, patient, and dedicated, she’s even a lesbian! When Precious hears Patton and her partner talk she says “they talk like a TV station I don’t watch.” Precious also gets support from a caring welfare case-worker, unglamorously played by Mariah Carey, who more than makes up for Glitter (I wonder how she took the news that her character would have a slight mustache).

Thus this film is very pro-government, the kind that would play well in the Obama White House but might draw suspicion from a “tea party.” I share the opinion that the system can work sometimes, but I doubt it’s this rosy. Of course, any pencil-pushing bureaucrat would seem like an angel when contrasted with the brutality of Precious’ mother, a character that ranks right up there with Medea and Joan Crawford in the pantheon of bad mothers. The greatness of Mo’Nique’s performance is that though this woman is vile there is a human being there–she has no visible redeeming features, but she is human. In the climactic scene, the best scene in the film, Mo’Nique lays bare the psyche of her character, and it’s not a pretty sight. But it’s certainly believable, given all the tabloid stories about abusive mothers through the years.

As for Ms. Sidibe, well, she’s remarkable. A woman who had never acted professionally before gives such an assured performance. At the start her face is a mask of impenetrability, but over the course of the film her features soften, and when she can finally laugh it’s as though a weight has been lifted from the audience. It can’t have been an easy thing to play–her character faces so many setbacks that it’s almost too much to bear, especially a medical one near the end of the film that felt like piling on. But I never found a false note in Sidibe’s work. I sincerely hope that this is not a one-shot deal for her.

Where the film suffers is in the over-direction by Lee Daniels. He tries to busy things up a bit too much. Precious has many daydreams, and they don’t always work, especially one where she inserts herself into an Italian film (I think it was Two Women). A scene showing bits and pieces of speeches by great black leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Shirley Chisholm seemed unnecessarily didactic, and I thought most of the scenes involving her classmates were like an updated version of Room 222.

There were some touches that were daring, and have created quite a fuss, particularly one in which Precious looks into the mirror and imagines her ideal self, and she sees a white girl. This has caused some consternation in the black press, and I can understand why. But I think the scene seems right, given that Precious hates herself as the film begins, and her walls are covered with posters of white stars like Stevie Nicks. It is also counterbalanced by a scene toward the end where Precious looks into a mirror and sees herself exactly as she is, which is also entirely appropriate.

I liked Precious, and give it a B, or three stars, whatever system you may choose. I wouldn’t call it one of the best of the year, although Oscar nominations for Sidibe and Mo’Nique will be well-deserved. But I think I was relieved to find that the film wasn’t simply a catalogue of ghetto misery.

Comments

Post a Comment