The Grapes of Wrath

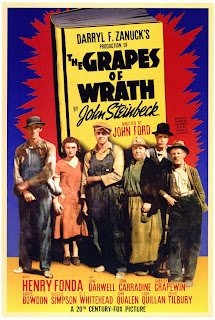

It was seventy years ago today that John Ford’s masterpiece The Grapes of Wrath was released. Based on the iconic novel by John Steinbeck, the film has become the cinematic representation of America during the Great Depression, but holds up just as well today, especially given the nervous economic conditions.

Operatic in structure, it tells the deceptively simple story of the Joad family, sharecroppers in Oklahoma, who have been walloped by a double-whammy: the economic crisis of the depression, and the ecological disaster of the dust bowl. When Tom, the prodigal son, arrives after four years in jail (for a murder in self-defense), he finds the homestead abandoned. Muley Graves, a neighbor, is holed up there, and tells Tom what’s going on–because of the erosion of the soil, the crops have failed, and the banks have kicked the farmers off of land they had occupied for generations. In a scene that is frighteningly current, a bulldozer shows up to knock over the Graves’ farm, driven by a neighbor, who needs the work. The bank is some nebulous threat, and Graves and his sons don’t know who to fight. “Who do we shoot?” they ask, in vain.

Tom finds his family at his uncle’s house. They are a no-nonsense bunch. Seeing Tom for the first time, his Ma shakes his hand in welcome. He’s just in time, as they are headed to California. There’s a handbill circulating offering work picking crops. They pile up an ancient jalopy, and along with Casy, an ex-preacher who Tom has befriended, hit the road. They travel along old Route 66, which Steinbeck called the “mother road,” but endure some hardship along the way, as both Grandpa and Grandma die, as they can not live when separated from the land. They also encounter kindness, such as in a diner where they are sold a loaf of bread for less than cost and a waitress gives the kids a price break on candy.

There are a lot of Biblical allusions to the film, none so much as when they reach the Colorado River. Pa looks to California across the water and calls it the “land of milk and honey.” As if in a baptism, the men take a dip into the water. But in the form of Casy, the religious talk isn’t always the Sunday sermon kind. When Tom finds him he is something like Christ, wandering in the wilderness, and he tells Tom: “Maybe there ain’t no sin and there ain’t no virtue, they’s just what people does,” which recalls Hamlet’s line, “There is no good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”

Steinbeck wrote the book after researching the migrant workers who picked fruit in the San Joaquin Valley during the thirties. Many of them were Okies, fleeing the devastation of their home state, and many of them suffered horrible poverty. The Joads find out that their dreams were naïve, with migrant camps run by the brutal hand of cops, wages kept low, with no where to shop but the company store. They leave one camp when Tom overhears that local hooligans plan on burning it down, so they move on and find work as scabs at another. Tom, who is a character defined by his rage (when he comes home Ma asks him, “are you mean mad?”) sees the injustice and is quick to fall in with the strikers. He ends up in a fracas and has to hide, and the Joads move on again.

Steinbeck was concerned that the film would soften the book, but was pleased with the result. The movie is more upbeat than the book, though. The Joads end up at a government-run camp, run by a Franklin Roosevelt look-a-like, and it is something of a cooperative paradise. The Joads are amazed to find running water, no cops, and even dances. It is at this dance that Tom memorably dances with his mother to the recurring musical theme of the film, “Red River Valley.”

But the authorities are still on Tom’s trail, and he realizes he must move on away from the family. Here he has his aria, one of the great speeches in American cinema. Ford, who used closeups sparingly, does move in tight to Tom in this instance, when he tells Ma: “I’ll be all around in the dark – I’ll be everywhere. Wherever you can look – wherever there’s a fight, so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad. I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry and they know supper’s ready, and when the people are eatin’ the stuff they raise and livin’ in the houses they build – I’ll be there, too.” As if this was thought to be too eloquent, Ma replies, “I don’t understand it, Tom.”

Ford wanted to end the film there, with Tom walking down the road in an extreme long-shot, silhouetted against the sunrise, but producer Darryl F. Zanuck wanted something more upbeat and definitive. So a dénouement was filmed, but not by Ford. The Joads are moving on to Fresno, where they hear there is twenty days work. Ma philosophizes how men and women handle adversity better, thinking that women see life as one long river. Then she chuckles and says, “Rich fellas come up an’ they die, an’ their kids ain’t no good an’ they die out. But we keep a’comin’. We’re the people that live. They can’t wipe us out; they can’t lick us. We’ll go on forever, Pa, ’cause we’re the people.”

It’s almost impossible, for me anyway, to think of some of these scenes without my tears duct wobbling. It is true that both Steinbeck and Ford were accused of sentimentality–Orson Welles called it Ford’s vice. But there is a difference if the sentiment is honest, and rooted in the characters. Here it serves to give the audience empathy. A scene in which Ma makes some stew and is surrounded by starving children, not sure if she has enough beyond her own family, is sentimental but illustrative of how we all make decisions like that all the time.

The cinematography was by Gregg Toland, who the next year would blaze a comet-like trail with his work on Citizen Kane. His photography of The Grapes of Wrath is no less brilliant. Ford said that it was beautifully shot, though there was nothing beautiful to shoot, and it recalls the era’s photographs by Dorothea Lange. Ford’s actors used no makeup, and you can see the years of hard work in their faces.

Ford won the Oscar for Best Directing (though the film itself lost to Rebecca for Best Picture). Jane Darwell won Best Supporting Actress as Ma (her best scene may have been a silent one early in the film, when she decides whether to keep or burn family treasures before they leave Oklahoma), but Henry Fonda, as Tom, did not win Best Actor. This is one of the most familiar Oscar screw-up stories. He lost to his good friend James Stewart, who had a smaller part in The Philadelphia Story. It’s widely believed that this was Oscar playing catch-up, as Stewart had lost the year before for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (beaten by Robert Donat in Goodbye, Mr. Chips). No doubt the Academy figured they’d make it up to Fonda later. They did, in his second nomination–forty-one years later for On Golden Pond.

The legacy of this film is long. Both Woody Guthrie and Bruce Springsteen wrote songs about Tom Joad, making him an almost supernatural figure, like the union organizer Joe Hill. Though the book was and is still banned in some places, the film wasn’t as controversial, and was even lauded by some of the right-wing. Richard Nixon was pleased because Soviets could see it and note that even poor families could afford to own a truck. It is be noted, though, that Steinbeck was adamantly anti-Communist. Ford’s politics were more complicated. He was a good liberal, but at the end of his life supported Nixon and the Vietnam War.

As I said, the book has a much more harrowing ending, reproduced in the stage version, mounted by the Steppenwolf Theater Company. I saw it on Broadway about twenty years ago (Gary Sinise played Tom). The Joads are living in a barn. The daughter Rose of Sharon has delivered a stillborn baby. They come across a starving man, and she offers her breast milk to him. To further emphasize the “family of man” theme, the stage version cast as African American as the stranger. Clearly the America of 1940 was not ready for such an image.

Comments

Post a Comment