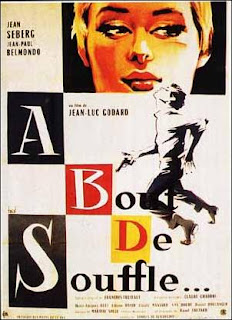

Breathless

This week marks the fiftieth anniversary of Breathless, the most revolutionary film, technique-wise, to be released since Citizen Kane. It was Jean-Luc Godard’s first feature-length film, and remains the most iconic film by the critics-turned-filmmakers of Cahier du Cinema, who would become known as the “French New Wave.” I have spent a rainy day watching the Criterion edition, and all the extras.

This week marks the fiftieth anniversary of Breathless, the most revolutionary film, technique-wise, to be released since Citizen Kane. It was Jean-Luc Godard’s first feature-length film, and remains the most iconic film by the critics-turned-filmmakers of Cahier du Cinema, who would become known as the “French New Wave.” I have spent a rainy day watching the Criterion edition, and all the extras.The film bears the name of three of them. In addition to Godard, Claude Chabrol is listed as “artistic advisor” and the script treatment is credited to Francois Truffaut. But these credits were smoke-screens, slapping the names of the more prominent New-Wavers on the poster to give the film some juice. Truffaut had hit it big with The 400 Blows, and Chabrol with Les Cousins. But in reality, it was all Godard, and some say that cinema can be broken into two parts: before Breathless, and after Breathless.

The New Wave was fascinated with American cinema, and Breathless (the literal translation of the title is “at breath’s end) is a marriage of the American crime picture with the European art film. The first to do this was Jean-Pierre Melville, who made Bob le Flambeur a few years earlier. Melville makes a key appearance in Breathless (more on that later), and the character of Bob is even mentioned during the film (someone mentions that he’s in the pen).

The story was conceived by Truffaut, who saw a news story about a car thief. We meet Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo) in Marseilles. He steals a car, but ends up chased by motorcyle policeman. He kills one of them, and flees to Paris, where a man owes him money. He hopes to collect and take his American girlfriend (Jean Seberg) to Italy. He is tracked by the police, and the net draws around him, and ultimately Seberg decides to turn him in, and he’s gunned down in the street.

This would be the simplest, most straight-forward plot Godard would ever film, but its execution was hardly conventional. The most radical element was the use of the jump-cut, which was almost accidental. The rough cut of the film was two and a half hours, far too long for Godard’s taste, so he hit upon cutting within the middle of the scene. Thus a scene with dialogue would be trimmed of the dead moments between words, so though the picture jumps, the dialogue (which was all dubbed–they did not shoot with synchronous sound) flowed uninterrupted. The effect gives the scenes a vital, kinetic rhythm that grabs the viewer immediately. The first, most ostentatious use of it is when Belmondo kills the policeman. We see a close-up of the gun, the trigger is pulled. Then, the policeman falls dead in the opposite direction of the way the gun is pointing (another rule violated), followed by Belmondo running across an open field. All of this is done in about three or four seconds, but the mind is quickly able to assemble the parts of the scene and intuit what happens. Another example is when Belmondo is driving around, with Seberg in the passenger seat. He tells her that he likes a girl with a pretty neck, pretty breasts, a pretty face, etc. The camera remains in the back seat, behind her left shoulder, but for each fragment of the sentence Belmondo says, the background of the scene changes. The effect is astonishingly embracing, and now used all the time.

There are many other audacious moments in the film, perhaps none so more than the famous, twenty-plus minute scene (or almost a third of the film) between Belmondo and Seberg in her cramped hotel room. The hotel room was so small that only the actors, Godard, his director of photography and the script supervisor were in the room (and the latter was on the balcony). There were no lights, no cables (Godard’s photographer, Raoul Coutard, used only available light). Godard had written the scene the night before, and the two actors improvised around the words, flirting and teasing and advancing and retreating. I think it’s one of the great love scenes ever filmed.

The film, though the story of a small-time crook and the American girl he falls in love with, manages to be about much more. Seberg is a woman who is from America but lives in Paris, but isn’t really at home in either culture. She hawks the New York Herald Tribune on the Champs-Elysee, but hopes to be a journalist. Though American, she represents high culture, fancying Chopin, Mozart, Picasso, and William Faulkner. Belmondo is of low culture, (his first line is, “After all, I’m an ass-hole”) reading nothing but the newspaper (there’s a funny scene when a girl selling copies of Cahiers du Cinema approaches him and asks if he believes in youth, but he sneers at her and says he likes old people) and worshipping Humphrey Bogart–he stops at a movie poster of one of Bogart’s films in the glass case at a cinema and regards it as a shrine, and has adopted Bogart’s move of running his thumb across his lip. He seems to have cultivated his style from detective movies, wearing his fedora cocked over his eyes, a cigarette dangling from his lips and saying things like “I always fall for women who aren’t my type.” But if Bogart is Poiccard’s idol Belmondo’s acting style is clearly modeled after Marlon Brando, who had set the acting world on fire in the 1950s.

Godard wrote the script as he went along, and there are some lines that make one wonder if it’s really deep or just really silly. There is a lot of circular Carrollinian nonsense, such as when Seberg says, “I don’t know if I’m unhappy because I’m not free, or if I’m not free because I’m unhappy.” The scene with Melville amplifies this by a thousand. He plays a novelist who gives a press conference at Orly airport. He is asked a lot of pretentious questions and gives enigmatic answers, like “Love is a form of eroticism, and vice versa.” When Seberg asks him what his greatest ambition is, he looks her in the eye and says, “To become immortal, and then die.”

Death is an ever-present theme in the film. Belmondo asks Seberg if she thinks about it, and when she quotes Faulkner she chooses the last line of Wild Palms: “Between grief and nothing I will take grief.” When Belmondo lies dying on the street at the end of the film, he looks up disgusted, and says, “Makes me want to puke.” (The French word is degueulasse, which can be variously translated as rotten or disgusting, but here is meant to suggest vomit). In a controversy that is reminiscent of the discussion of what Bill Murray whispers to Scarlett Johansson at the end of Lost in Translation, we don’t know if Belmondo means that his situation in general makes him want to puke, or whether it’s Seberg, now standing over him, who has disgusted him. He, after all, fell in love with her, despite his instincts, and she betrayed him. Seberg, who speaks French but is also always asking Belmondo what a particular idiom means, asks the policeman what he said, and he responds, “You make him want to puke.” Then Seberg, who had such a magnificent face, and whose gamine appearance would set the pace for fashion throughout the sixties, from Mia Farrow to Twiggy to Edie Sedgwick, asks, “Qu’est-ce que c’est ‘degueulesse?’” (“What does ‘puke’ mean?”) She then looks straight into the camera and runs her thumb across her lips, Bogart-style, as if sealing them.

I’ve seen this film several times, and I could almost convince myself to watch it again right now, even though I’ve already watched it once today. It remains as vital as it certainly was fifty years ago. It made Belmondo a big star, but sadly Jean Seberg struggled for the rest of her career, and committed suicide at the age of 40. Godard continues to make films, and some of them, like Contempt, Band of Outsiders, Week-End and Masculin/Feminin, were also strikingly original, but in many ways his crowning achievement remains his very first film.

Comments

Post a Comment