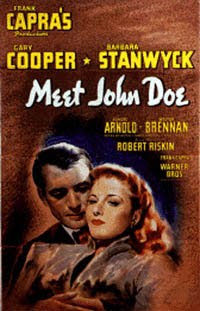

Meet John Doe

The third film in Frank Capra's "common man" trilogy is Meet John Doe, from 1941. Though similar in many respects to the other two films, it differs in many ways, particularly in tone. I found it to be much darker than Mr. Deeds or Mr. Smith, and I can only imagine this reflected the situation in Europe.

The third film in Frank Capra's "common man" trilogy is Meet John Doe, from 1941. Though similar in many respects to the other two films, it differs in many ways, particularly in tone. I found it to be much darker than Mr. Deeds or Mr. Smith, and I can only imagine this reflected the situation in Europe.Barbara Stanwyck stars as yet another career-girl, a newspaper columnist who has just been given a pink-slip. In desperation, she crafts a phony letter from a man calling himself John Doe, who is so disgusted with society that he announces he will throw himself off the roof of city hall on Christmas Eve. The column ignites such an interest that she gets her job back, and even after the paper's brass (in the form of managing editor James Gleason) finds out she made him up, they continue the ruse. They need to find a person to play the part of John Doe, though, and a cavalcade of hobos descends on the paper's office. Stanwyck is immediately drawn to a washed up ballplayer, Gary Cooper, and he takes the gig, though his friend, Walter Brennan, who mistrusts anyone with a bank account, protests.

Cooper, giving speeches written by Stanwyck, is so popular with his common-sense shtick that he is a sensation. The paper's owner, Edward Arnold (in another sinister performance) senses the power of Cooper's act, and starts a series of clubs centered around his message of love thy neighbor. They pop up all over the country, and Cooper becomes a folk hero. Arnold wants to use Cooper as a puppet, intending to spring himself to the White House, but when Cooper finds out he threatens to expose Arnold. In a rally at a stadium in a rainstorm, Arnold's hired goons interrupt Cooper and he is exposed as a fraud. Come Christmas Eve, the cast reassembles on top of city hall, wondering if Cooper will jump after all.

Compared with Deeds and Smith, Meet John Doe seems a little more forced and doesn't work quite as well. The overlay of the spectre of fascism is a bit chilling. Cooper's down-home charm is fine, and there's a real anger behind it when he finds out he's been played for a sucker. There are a number of fine scenes, including one where Gleason, who has seen the error of his ways, drunkenly tips Cooper as to Arnold's intentions.

The film could also be considered a warning against the misuse of populism, a theme that would be re-explored in Elia Kazan's terrific A Face in the Crowd, or in real life situations like the recent Joe the Plumber. Almost without fail, whether fictional or real, folk heroes are seldom what they appear to be.

Though once again common decency triumphs, the victory is less clear cut, as Arnold is still powerful--the victory is more moral than tangible. And for the first but not last time Capra ends a picture with the sound and image of Christmas bells, which would of course end his valedictory film, It's a Wonderful Life.

Comments

Post a Comment