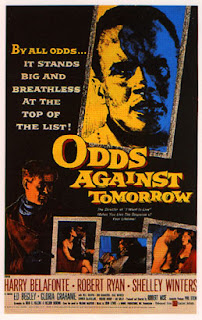

Odds Against Tomorrow

The first noir to use a black protagonist, Odds Against Tomorrow, which I've seen twice now, is a crackerjack entertainment that is also ahead of its time on its views of racial issues. Essentially using the classic heist template, it advances it by being an adept character study of two men of opposition who are forced to collaborate.

The film, from 1959, stars Harry Belafonte and was produced by his company. The direction is by Robert Wise. The real star, though, is Robert Ryan, who sizzles as a racist who is a man out of his time. The film begins with him living in domestic misery with Shelley Winters. He's an ex-con and she earns the money, while he's left picking up her dry cleaning and babysitting for the upstairs neighbor (Gloria Grahame, in a brief but vivid performance).

Ed Begley, an ex-cop who did a year for contempt of court for not naming names, has an idea. For reasons not explained, he knows about the routine of a bank in Upstate New York (the movie was filmed in New York City and Hudson, New York). He approaches Ryan, who turns him down, telling him he's not a thief. He also approaches Belafonte, a jazz musician who is in the local mob boss for betting on the horses. Begley manipulates the mob boss into pressing Belafonte for payment.

The first half of the film is basically the two men realizing they have no other choice but to accept Begley's offer, and it's spelled out in terrific scenes. Belafonte gets drunk at the jazz club (few films of the era had so many black faces in them) while Ryan is bullied by a young soldier (Wayne Rogers) in a bar.

The robbery itself only encompasses the last thirty minutes or so of the film, and of course, in the grand tradition of heist movies (a favorite genre of mine) something doesn't go as planned. Ryan and Belafonte are at each other's throats, and Ryan's inability to see past Belafonte's color screws up the whole thing. In a pointed finale, the two men's races are rendered moot.

Also everything about this movie has crackle, including the script by blacklisted Abraham Polonsky (who was fronted at the time by black novelist John O. Killens--Polonsky has since been given official credit) cinematography by John C. Brun, editing by Dede Allen and a jazz score by John Lewis (including such luminaries as Percy Heath, Bill Evans and Milt Jackson). There's also a small but interesting performance by Richard Bright as a henchman who I believe is supposed to be gay, but of course that was too early to be forthright about such a thing.

The film, from 1959, stars Harry Belafonte and was produced by his company. The direction is by Robert Wise. The real star, though, is Robert Ryan, who sizzles as a racist who is a man out of his time. The film begins with him living in domestic misery with Shelley Winters. He's an ex-con and she earns the money, while he's left picking up her dry cleaning and babysitting for the upstairs neighbor (Gloria Grahame, in a brief but vivid performance).

Ed Begley, an ex-cop who did a year for contempt of court for not naming names, has an idea. For reasons not explained, he knows about the routine of a bank in Upstate New York (the movie was filmed in New York City and Hudson, New York). He approaches Ryan, who turns him down, telling him he's not a thief. He also approaches Belafonte, a jazz musician who is in the local mob boss for betting on the horses. Begley manipulates the mob boss into pressing Belafonte for payment.

The first half of the film is basically the two men realizing they have no other choice but to accept Begley's offer, and it's spelled out in terrific scenes. Belafonte gets drunk at the jazz club (few films of the era had so many black faces in them) while Ryan is bullied by a young soldier (Wayne Rogers) in a bar.

The robbery itself only encompasses the last thirty minutes or so of the film, and of course, in the grand tradition of heist movies (a favorite genre of mine) something doesn't go as planned. Ryan and Belafonte are at each other's throats, and Ryan's inability to see past Belafonte's color screws up the whole thing. In a pointed finale, the two men's races are rendered moot.

Also everything about this movie has crackle, including the script by blacklisted Abraham Polonsky (who was fronted at the time by black novelist John O. Killens--Polonsky has since been given official credit) cinematography by John C. Brun, editing by Dede Allen and a jazz score by John Lewis (including such luminaries as Percy Heath, Bill Evans and Milt Jackson). There's also a small but interesting performance by Richard Bright as a henchman who I believe is supposed to be gay, but of course that was too early to be forthright about such a thing.

Comments

Post a Comment