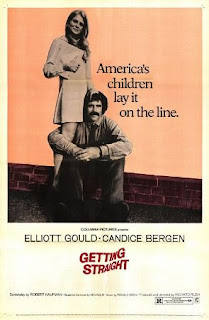

Getting Straight

Getting Straight is a real museum piece, an artifact from the student protest days of the late '60s and early '70s, as quaint as a peace medallion or a fringed vest. It has flashes of brilliance, but is wildly uneven and often as self-indulgent as the characters it portrays.

Directed by Richard Rush, who made a similarly uneven film The Stunt Man, it stars Elliot Gould as Harry Bailey, a college student at a large state university. He is older than most of the students, as he did a tour in Vietnam and participated in protests (he was at Selma, he tells a black activist). Done with activism, he wants to get his master's and teaching certificate, but lives on the margins, getting evicted from his apartment and driving a car that is one jolt away from dilapidation.

He is still a BMOC, though, knowing almost everyone, who all want a piece of his time. One of his friends is Nick, (Robert F. Lyons), who is baked most of the time and is desperately trying to get a deferment from the draft--feigning homosexuality or taking up Buddhism doesn't work.

Gould's girlfriend is Candice Bergen, a girl from privilege who vacillates between protest and wanting to settle down in the suburbs with a bland gynecologist. She and Gould fight most of the time, as Gould, like many men on the left in those days, was still Chauvinistic, and demanded that she do his laundry.

Viewed today, Getting Straight is an interesting time capsule of college life in the countercultural movement. Gould has one foot in the student world and one in the administration world--he is hired as something of a bridge between the two--and his obstinate nature makes him argue the opposite side of who he's with. Gould gives a large performance, sometimes too far over the top, such as his breakdown during his orals when he is challenged to agree that The Great Gatsby was about homosexual panic.

Parts of this film are very intense, such as protest that ends up a riot, with police clubbing the students. Then National Guard are called in, and it's worth noting that the film was released only nine days after the shootings at Kent State, so they must have really resonated. The film is hard on both sides, with the university president, a self-professed liberal, only willing to have a Negro History Week and lifting the curfew by one hour (Gould points out the window at a student throwing rocks, telling the president, "Two weeks ago he just wanted to get laid. Now he wants to kill somebody. You should have let him get laid.")

But the protesters are presented just as callowly. The black activist (Max Julien) comes across as strident, though all he wants is a black studies department, which in retrospect seems minor. Gould finds their rhetoric irrelevant, and simply wants to get his teaching degree, but a professor (Jeff Corey) stands in his way.

A few other things: Bergen, who went on to a great career in Murphy Brown, gives an epically bad performance, wailing her lines as if she were sitting on pins. It's amazing that she was able to overcome her awfulness this early in her career. Also, Harrison Ford has a few scenes as a student, and it's hard to think of him as so young.

Directed by Richard Rush, who made a similarly uneven film The Stunt Man, it stars Elliot Gould as Harry Bailey, a college student at a large state university. He is older than most of the students, as he did a tour in Vietnam and participated in protests (he was at Selma, he tells a black activist). Done with activism, he wants to get his master's and teaching certificate, but lives on the margins, getting evicted from his apartment and driving a car that is one jolt away from dilapidation.

He is still a BMOC, though, knowing almost everyone, who all want a piece of his time. One of his friends is Nick, (Robert F. Lyons), who is baked most of the time and is desperately trying to get a deferment from the draft--feigning homosexuality or taking up Buddhism doesn't work.

Gould's girlfriend is Candice Bergen, a girl from privilege who vacillates between protest and wanting to settle down in the suburbs with a bland gynecologist. She and Gould fight most of the time, as Gould, like many men on the left in those days, was still Chauvinistic, and demanded that she do his laundry.

Viewed today, Getting Straight is an interesting time capsule of college life in the countercultural movement. Gould has one foot in the student world and one in the administration world--he is hired as something of a bridge between the two--and his obstinate nature makes him argue the opposite side of who he's with. Gould gives a large performance, sometimes too far over the top, such as his breakdown during his orals when he is challenged to agree that The Great Gatsby was about homosexual panic.

Parts of this film are very intense, such as protest that ends up a riot, with police clubbing the students. Then National Guard are called in, and it's worth noting that the film was released only nine days after the shootings at Kent State, so they must have really resonated. The film is hard on both sides, with the university president, a self-professed liberal, only willing to have a Negro History Week and lifting the curfew by one hour (Gould points out the window at a student throwing rocks, telling the president, "Two weeks ago he just wanted to get laid. Now he wants to kill somebody. You should have let him get laid.")

But the protesters are presented just as callowly. The black activist (Max Julien) comes across as strident, though all he wants is a black studies department, which in retrospect seems minor. Gould finds their rhetoric irrelevant, and simply wants to get his teaching degree, but a professor (Jeff Corey) stands in his way.

A few other things: Bergen, who went on to a great career in Murphy Brown, gives an epically bad performance, wailing her lines as if she were sitting on pins. It's amazing that she was able to overcome her awfulness this early in her career. Also, Harrison Ford has a few scenes as a student, and it's hard to think of him as so young.

Comments

Post a Comment