Cronos

As I embark on this excursion into Mexican culture, of course I will take a look at cinema. Mexican cinema goes almost as far back as any other nation's cinema--several silent films were made in Mexico, almost all of which are lost. A "golden age" in the 1930's and '40s saw a thriving Mexican film industry, and produced one of the most popular stars in the world--Catinflas, who was kind of the Latin Charlie Chaplin. Most of these films were slapstick comedies or melodramas that prefigured today's Telenovas, and none are particularly noted for their artistic greatness.

The '60s saw the stardom of El Santo, a wrestler who wore a distinctive mask (not to belittle Mexican culture, but I think the Mexican wrestling mask is one of their great contributions). Lately, there has been a renaissance of Mexican films, with directors like Alfonso Cuaron, Arturo Ripstein, and Alejandro Gonzales Innaritu, some of whom have made the jump to Hollywood. Their is also Luis Bunuel, who though a Spaniard, has made movies in Mexico.

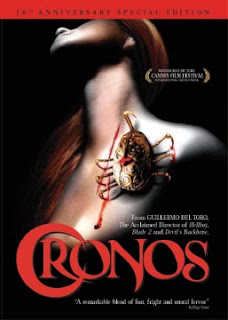

But the most popular film director to come from Mexico is Guillermo Del Toro, and his first film was Cronos, a delightfully creepy horror film. In taking a look at this movie so soon after Pacific Rim, I'm struck that Del Toro works better with a low budget. This film, with minimal special effects (but some great makeup) evokes a far better atmosphere that Pacific Rim, or either of the Hellboy pictures (which I liked both of). Although Cronos isn't as good as The Devil's Backbone or Pan's Labyrinth, it's clear from the beginning that Del Toro has abundant talent.

The film begins with a kind of clunky prologue, in which a sixteenth-century alchemist creates a "cronos device," which is a gold thing that looks like a scarab. It grants the user immortality, at least to most things, as the alchemist ends up dying in the 1930s when a bank vault collapses.

The device ends up inside a state of an archangel, which is in the possession of a kindly old antiques dealer, (Federico Luppi), who dotes on his very quiet granddaughter. They end up finding the device, which Luppi accidentally uses, and though it's painful (it pierces the flesh) he gets hooked on feeling youthful.

Meanwhile, the device is sought after by a rich industrialist (Claudio Brook), who employs his hapless but strong nephew (Ron Perlman) to do his bidding. Perlman buys the statue, but when it turns up empty, he comes after Luppi, who is looking younger and younger. After Perlman kills Luppi, we see just how powerful the device is.

Del Toro, who also wrote the script, gives the film incredible life. Perlman's character, a lummox who is brow-beaten by his uncle and wants a nose job, is a marvel of ingenuity by both actor and writer. The use of the granddaughter, who looks on silently as her grandfather succumbs to vampiric madness (it seems that a side effect of the device is craving human blood) is effectively creepy. There are also some great scenes inside a mortuary, which show more than I care to know about the art and science of preparing a body.

Del Toro's next film was Mimic, which I saw but don't remember much about. The only film of his I haven't seen is Blade II, but since I didn't see Blade I don't feel an urge to do so. In the extras, Del Toro gives us a tour of his extra house, Bleak House, which holds his vast collection of books and toys dealing with horror and fantasy films. As it so often happens, film directors are really kids who have never entirely grown up.

The '60s saw the stardom of El Santo, a wrestler who wore a distinctive mask (not to belittle Mexican culture, but I think the Mexican wrestling mask is one of their great contributions). Lately, there has been a renaissance of Mexican films, with directors like Alfonso Cuaron, Arturo Ripstein, and Alejandro Gonzales Innaritu, some of whom have made the jump to Hollywood. Their is also Luis Bunuel, who though a Spaniard, has made movies in Mexico.

But the most popular film director to come from Mexico is Guillermo Del Toro, and his first film was Cronos, a delightfully creepy horror film. In taking a look at this movie so soon after Pacific Rim, I'm struck that Del Toro works better with a low budget. This film, with minimal special effects (but some great makeup) evokes a far better atmosphere that Pacific Rim, or either of the Hellboy pictures (which I liked both of). Although Cronos isn't as good as The Devil's Backbone or Pan's Labyrinth, it's clear from the beginning that Del Toro has abundant talent.

The film begins with a kind of clunky prologue, in which a sixteenth-century alchemist creates a "cronos device," which is a gold thing that looks like a scarab. It grants the user immortality, at least to most things, as the alchemist ends up dying in the 1930s when a bank vault collapses.

The device ends up inside a state of an archangel, which is in the possession of a kindly old antiques dealer, (Federico Luppi), who dotes on his very quiet granddaughter. They end up finding the device, which Luppi accidentally uses, and though it's painful (it pierces the flesh) he gets hooked on feeling youthful.

Meanwhile, the device is sought after by a rich industrialist (Claudio Brook), who employs his hapless but strong nephew (Ron Perlman) to do his bidding. Perlman buys the statue, but when it turns up empty, he comes after Luppi, who is looking younger and younger. After Perlman kills Luppi, we see just how powerful the device is.

Del Toro, who also wrote the script, gives the film incredible life. Perlman's character, a lummox who is brow-beaten by his uncle and wants a nose job, is a marvel of ingenuity by both actor and writer. The use of the granddaughter, who looks on silently as her grandfather succumbs to vampiric madness (it seems that a side effect of the device is craving human blood) is effectively creepy. There are also some great scenes inside a mortuary, which show more than I care to know about the art and science of preparing a body.

Del Toro's next film was Mimic, which I saw but don't remember much about. The only film of his I haven't seen is Blade II, but since I didn't see Blade I don't feel an urge to do so. In the extras, Del Toro gives us a tour of his extra house, Bleak House, which holds his vast collection of books and toys dealing with horror and fantasy films. As it so often happens, film directors are really kids who have never entirely grown up.

Comments

Post a Comment