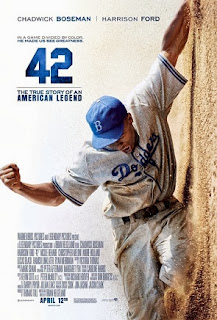

42

Aside from Martin Luther King, Jr., the most important person in the U.S. civil rights movement was Jackie Robinson. When he broke the color barrier in Major League baseball in 1947, it was a quantum leap forward in the perception of blacks in America, and though it would take several decades to gain the equality that blacks have now, Robinson's courage planted the seed.

In 42, a decent but frustrating film by Brian Helgeland, the hero of the day is really Branch Rickey, the president of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who put himself on the line to champion Robinson. There is certainly a truth to this--without a white general manager to sign a black player, nothing would have happened--I wonder at the golden glow that surrounds Rickey in this film, while Robinson, though exhibiting remarkable restraint, is almost second-fiddle.

Rickey, played by a hammy Harrison Ford, is determined to sign a black player. He and his assistants pore over the resumes of great black players, and they pass over a few for various reasons: Satchel Paige too old, Roy Campanella too sweet-natured. Josh Gibson, perhaps the greatest hitter in Negro League history, isn't mentioned, but he was passed over for being too unstable (he would die in 1947).

Robinson is chosen because he played in integrated sports in college, and though tough, he can keep his poise when it's necessary. Robinson, played well by Chadwick Boseman, is of course overjoyed at the prospect, and proposes to his girlfriend Rachel (Nicole Behairie). He starts at the minor league team in Montreal, but he will really have to put up with shit when he gets to the majors. It starts with his own team--a petition is drawn up that the Dodgers won't play with him.

Then the manager, Leo Durocher (Chris Meloni) is suspended for immoral behavior (laughable as that is today). Burt Shotton (Max Gail, Wojo from the old Barney Miller show) is dragged out of retirement, and slowly the Dodgers realize Robinson will help them win. His most visible supporters were Eddie Stanky, Ralph Branca, and Pee Wee Reese (Lucas Black), though a son of the south, sees the injustice and makes a public gesture by putting his arm around Robinson during warm-ups at a game in Cincinnati.

There's some pretty disturbing stuff in this film. A diatribe of invective by Phillies manager Ben Chapman (Alan Tudyk) is pretty hard to take, and reduces Robinson to tears in the dugout runway. Rickey comforts him, in a scene that smacks of Hollywood revisionism, but it is true that this was why Robinson was chosen--he wasn't the best Negro League player, but he was able to hold in his rage.

The film gets the baseball right, and as far as I know it doesn't rewrite the facts as far as games are concerned. For example, Robinson doesn't get a home run in his first at bat--he walks. But then he steals second, third, and scores on a balk when he rattles the pitcher. The actors look good playing--it never occurred to me that they weren't doing things correctly.

But the emphasis on Rickey here is a bit puzzling. The narrative spine of the film isn't whether Robinson will make the majors--that happens halfway through--but why Rickey is doing it. He keeps saying that it's all business, and certainly the Dodgers' willingness to sign black players kept them in the upper division for a generation. But a speech near the end when Rickey reveals an incident from his pass is oatmeal psychology. Even if it's true it's too pat.

But, as baseball movies go, 42 isn't bad. We still haven't had the movie Robinson deserves, though.

In 42, a decent but frustrating film by Brian Helgeland, the hero of the day is really Branch Rickey, the president of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who put himself on the line to champion Robinson. There is certainly a truth to this--without a white general manager to sign a black player, nothing would have happened--I wonder at the golden glow that surrounds Rickey in this film, while Robinson, though exhibiting remarkable restraint, is almost second-fiddle.

Rickey, played by a hammy Harrison Ford, is determined to sign a black player. He and his assistants pore over the resumes of great black players, and they pass over a few for various reasons: Satchel Paige too old, Roy Campanella too sweet-natured. Josh Gibson, perhaps the greatest hitter in Negro League history, isn't mentioned, but he was passed over for being too unstable (he would die in 1947).

Robinson is chosen because he played in integrated sports in college, and though tough, he can keep his poise when it's necessary. Robinson, played well by Chadwick Boseman, is of course overjoyed at the prospect, and proposes to his girlfriend Rachel (Nicole Behairie). He starts at the minor league team in Montreal, but he will really have to put up with shit when he gets to the majors. It starts with his own team--a petition is drawn up that the Dodgers won't play with him.

Then the manager, Leo Durocher (Chris Meloni) is suspended for immoral behavior (laughable as that is today). Burt Shotton (Max Gail, Wojo from the old Barney Miller show) is dragged out of retirement, and slowly the Dodgers realize Robinson will help them win. His most visible supporters were Eddie Stanky, Ralph Branca, and Pee Wee Reese (Lucas Black), though a son of the south, sees the injustice and makes a public gesture by putting his arm around Robinson during warm-ups at a game in Cincinnati.

There's some pretty disturbing stuff in this film. A diatribe of invective by Phillies manager Ben Chapman (Alan Tudyk) is pretty hard to take, and reduces Robinson to tears in the dugout runway. Rickey comforts him, in a scene that smacks of Hollywood revisionism, but it is true that this was why Robinson was chosen--he wasn't the best Negro League player, but he was able to hold in his rage.

The film gets the baseball right, and as far as I know it doesn't rewrite the facts as far as games are concerned. For example, Robinson doesn't get a home run in his first at bat--he walks. But then he steals second, third, and scores on a balk when he rattles the pitcher. The actors look good playing--it never occurred to me that they weren't doing things correctly.

But the emphasis on Rickey here is a bit puzzling. The narrative spine of the film isn't whether Robinson will make the majors--that happens halfway through--but why Rickey is doing it. He keeps saying that it's all business, and certainly the Dodgers' willingness to sign black players kept them in the upper division for a generation. But a speech near the end when Rickey reveals an incident from his pass is oatmeal psychology. Even if it's true it's too pat.

But, as baseball movies go, 42 isn't bad. We still haven't had the movie Robinson deserves, though.

Comments

Post a Comment