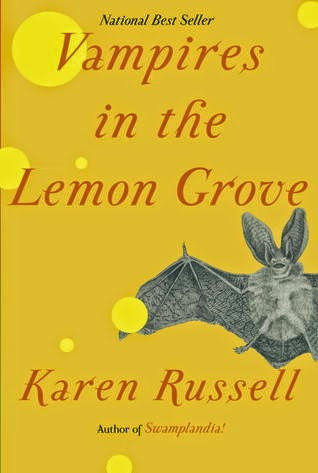

Vampires in the Lemon Grove

I've read almost all of Karen Russell's brief but dynamic output, and the more I read the more I'm a fan. Her latest short story collection, Vampires in the Lemon Grove, contains eight examples of her wickedly bent imagination, with each story containing some measure of magic realism, some much more than others.

The opening and title story, for example, is another spin on vampires, but manages to be different. In this instance, vampires feed on lemons. Two ancient vampires, who as far as they know are the only two of their kind, live in an Italian village and feed off the lemons, although the weakness for human flesh is not entirely abated. "Most people mistake me for a small, kindly Italian grandfather, a nonno. I have an old nonno's coloring, the dark walnut stain peculiar to southern Italians, a tan that won't fade away until I die (which I never will). I wear a neat periwinkle shirt, a canvas sunhat, black suspenders that sag at my chest. My loafers are battered but always polished. The few visitors to the lemon grove who notice me smile blankly into my raisin face and catch the whiff of some sort of tragedy; they whisper that I am a widower, or an old man who has survived his children. They never guess I am a vampire."

A few of the stories are out-and-out funny, like New Yorker casuals. In "Douglas Shackleton's Rules for Antarctic Tailgating" Russell imagines the fans of the krill, who in their millennia-long battle against the whales never win, but yet the fans keep coming and tailgating. It's a pretty good satire of the modern football fan. "So how to get ready for the big game? Say farewell to your loved ones. Notarize your will. Transfer what money you've got into trust for the kids. You'll probably want to put on some weight for the ride down to the ice caves; a beer gut has made the difference between life and death at the blue bottom of the world. Eat a lot of Shoney's and Big Boy and say your prayers."

In "The Barn at the End of Our Term," Russell imagines that ex-presidents have been reincarnated as horses. But not the most famous presidents. Hear, Rutherford B. Hayes and James Buchanan reside there, not Washington or Lincoln.

But most of the stories, beyond their creative settings or plots, have urgent poignancy. "Reeling for the Empire" concerns women who have mutated into silkworms: "I'll put it bluntly: we are all becoming reelers. Some kind of hybrid creature, part kaiko, silkworm caterpillar,and part human female." This is, of course, a commentary on the use of women in the workplace, but also inordinately creepy.

"Proving Up" is another creepy story, this time a Western, about a boy's ride across the desolate prairie of Nebraska to deliver a glass window. "The New Veterans" is about a masseuse who manages to help a vet with PTSD by manipulating his tattoo. And "The Seagull Army Descends on Strong Beach, 1979," is about a teenage boy who somehow sees the invasion of seabirds as some kind of metaphor for his life. "Cousin Steve was participating in a correspondence course with a beauty school in Nevada, America, and to pass his Radical Metamorphosis II course, he decided to dye Nal's head a vivid blue and then razor the front into tentacle-like bangs. 'Radical,' Nal said dryly as Steve removed the foil. Cousin Steve then had to airmail a snapshot of Nal's ravaged head to the United States desert, $17.49 in postage, so that he could get his diploma. In the photograph, Nal looks like he is going stoically to his death in the grip of a small blue octopus." When I read a paragraph like that, I just purr.

The tour de force of the collection, and the anchor leg, is "The Graveless Doll of Eric Mutis," which is about a group of bullies that find a scarecrow tied to a tree in a park in their urban New Jersey hell. "A scarecrow did not belong in our city of Anthem, New Jersey. Anthem had no crops, no silos, no crows--it had turquoise Port-o-Pottys and neon alleys, construction pits, dogs in purses, homeless women with powerful smells and opinions, garbage dumps haunted by white pigeons; it had our school, the facade of which was covered by a glorious psychedelic phallus mosaic, a bunch of spray-painted dicks. Cops leaned against the cement walls, not straw guards."

The boys realize the scarecrow looks like a boy the mercilessly picked on, but who disappeared. The ingenuity of this story is that Russell tells it from the bully's point of view, and he becomes ourselves, and we can empathize with him. At least I could.

Karen Russell is only 33. I am jealous and extremely admiring.

The opening and title story, for example, is another spin on vampires, but manages to be different. In this instance, vampires feed on lemons. Two ancient vampires, who as far as they know are the only two of their kind, live in an Italian village and feed off the lemons, although the weakness for human flesh is not entirely abated. "Most people mistake me for a small, kindly Italian grandfather, a nonno. I have an old nonno's coloring, the dark walnut stain peculiar to southern Italians, a tan that won't fade away until I die (which I never will). I wear a neat periwinkle shirt, a canvas sunhat, black suspenders that sag at my chest. My loafers are battered but always polished. The few visitors to the lemon grove who notice me smile blankly into my raisin face and catch the whiff of some sort of tragedy; they whisper that I am a widower, or an old man who has survived his children. They never guess I am a vampire."

A few of the stories are out-and-out funny, like New Yorker casuals. In "Douglas Shackleton's Rules for Antarctic Tailgating" Russell imagines the fans of the krill, who in their millennia-long battle against the whales never win, but yet the fans keep coming and tailgating. It's a pretty good satire of the modern football fan. "So how to get ready for the big game? Say farewell to your loved ones. Notarize your will. Transfer what money you've got into trust for the kids. You'll probably want to put on some weight for the ride down to the ice caves; a beer gut has made the difference between life and death at the blue bottom of the world. Eat a lot of Shoney's and Big Boy and say your prayers."

In "The Barn at the End of Our Term," Russell imagines that ex-presidents have been reincarnated as horses. But not the most famous presidents. Hear, Rutherford B. Hayes and James Buchanan reside there, not Washington or Lincoln.

But most of the stories, beyond their creative settings or plots, have urgent poignancy. "Reeling for the Empire" concerns women who have mutated into silkworms: "I'll put it bluntly: we are all becoming reelers. Some kind of hybrid creature, part kaiko, silkworm caterpillar,and part human female." This is, of course, a commentary on the use of women in the workplace, but also inordinately creepy.

"Proving Up" is another creepy story, this time a Western, about a boy's ride across the desolate prairie of Nebraska to deliver a glass window. "The New Veterans" is about a masseuse who manages to help a vet with PTSD by manipulating his tattoo. And "The Seagull Army Descends on Strong Beach, 1979," is about a teenage boy who somehow sees the invasion of seabirds as some kind of metaphor for his life. "Cousin Steve was participating in a correspondence course with a beauty school in Nevada, America, and to pass his Radical Metamorphosis II course, he decided to dye Nal's head a vivid blue and then razor the front into tentacle-like bangs. 'Radical,' Nal said dryly as Steve removed the foil. Cousin Steve then had to airmail a snapshot of Nal's ravaged head to the United States desert, $17.49 in postage, so that he could get his diploma. In the photograph, Nal looks like he is going stoically to his death in the grip of a small blue octopus." When I read a paragraph like that, I just purr.

The tour de force of the collection, and the anchor leg, is "The Graveless Doll of Eric Mutis," which is about a group of bullies that find a scarecrow tied to a tree in a park in their urban New Jersey hell. "A scarecrow did not belong in our city of Anthem, New Jersey. Anthem had no crops, no silos, no crows--it had turquoise Port-o-Pottys and neon alleys, construction pits, dogs in purses, homeless women with powerful smells and opinions, garbage dumps haunted by white pigeons; it had our school, the facade of which was covered by a glorious psychedelic phallus mosaic, a bunch of spray-painted dicks. Cops leaned against the cement walls, not straw guards."

The boys realize the scarecrow looks like a boy the mercilessly picked on, but who disappeared. The ingenuity of this story is that Russell tells it from the bully's point of view, and he becomes ourselves, and we can empathize with him. At least I could.

Karen Russell is only 33. I am jealous and extremely admiring.

Comments

Post a Comment