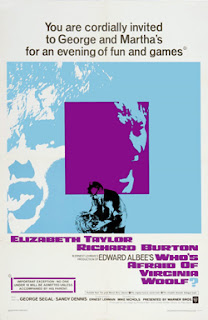

Who's Afraid of Virgina Woolf (1966)

I had planned to write about the film adaptation of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf toward the end of the year, when I annually discuss the nominees for the Best Picture Oscar from fifty years ago. But then Edward Albee, who wrote the play it is based on, up an died, and I realized I'm the only one who sets the rules for this blog, so I'm moving up the date.

As I mentioned in my review of the revival on Broadway a few years ago, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf is my favorite play. Albee, following the death of Eugene O'Neill and the kind of petering out of Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller, assumed the mantle of America's playwright. Ben Brantley in the Times think he held it until Tony Kushner's Angels in America, but I might stick up for Sam Shepard. In any event, Albee was a giant of American dramatists, and Virginia Woolf was his masterpiece.

It was a sensation on Broadway, both hated and worshiped, and was made into a film by Mike Nichols. It was Nichols' first film, after an amazing run on Broadway that saw five of his plays running at the same time. But mostly he did Neil Simon and other light fare. Virginia Woolf was as dark as a moonless night. He was also working with, at the time, the most famous people in the world, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton.

The film version is very, very good, but shows the pitfalls of taking a play that is perfect as it is and trying to adapt it for cinema. The play takes one in one living room in almost real time. Some films that are adapted for films that don't "break out" are often called "stagey," because cinema is supposed to be expansive. Who decided this, I don't know. So what Nichols did is very daring. He did break out, but the script, written by producer Ernest Lehman, adds almost nothing. Albee joked that he added one line and was paid a million dollars. What Lehman and Nichols did was try to turn it into a movie.

To those who are too young or too isolated to know the story, it is about four people who are like scorpions in a bottle. George and Martha, probably not coincidently named for the father and mother of our country, are Burton and Taylor. He's an ineffectual, intellectual history professor, she's the blousy daughter of the president of the college (in the play she's older than George, but I suppose no one would believe Taylor was older than Burton). They have returned from a faculty party, and bicker as if it were second nature (she wants to know where the line "What a dump!" comes from. It is never answered, but for trivia buffs it is Bette Davis in Beyond the Forest). It is two in the morning, but Taylor has invited a young faculty member, George Segal, and his wife, Sandy Dennis, over for a nightcap. Thus begin the games.

What follows is some of the most bilious dialogue ever written for the American stage, or for the American screen. Burton and Taylor have something of an understanding in their marriage--they constantly fight--"If you existed I'd divorce you," Taylor tells him, but Segal and Dennis don't quite understand it. Segal, whom Taylor pointedly seduces, is a biologist, whom Burton mistrusts--he's convinced biology will make everyone the same, and end all creativity--ooks askance at the sideshow he's watching. Dennis quickly gets drunk on brandy, and is mocked for her "slim hips" and being a "simp." When she later twirls herself around in a road house, shouting "I dance like the wind," or claps shouting "Violence! Violence!" you both feel sorry for her and hate her.

There's a point you hate everyone in this play, but also feel the deepest empathy. Albee, during his whole career, peeled back the facade, especially of academic and upper-middle-class types. In this play, the skeleteons in the closet are practically dancing--at the center of the play is the supposed son of Burton and Taylor. Though this story is over fifty years old, I choose not to reveal it here.

Nichols and Lehman kept Albee's vitriolic language. It often has the sound of percussion, with the repetition of words like "flop," and "snap!" The insults are often laugh out-loud funny, even when the cut to the bone. Burton says to Taylor: "And please keep your clothes on, too. There aren't many more sickening sights in this world than you with a few drinks in you and your skirt up over your head." They keep the three act structure, with each being a game--"Humiliate the Host," "Get the Guests," ("Hump the Hostess" happens off screen) and then "Bringing Up Baby."

But where the film goes a little off the rails is the scene at the roadhouse. This is where "Get the Guests" is played, where Burton reveals what Segal told him--that he married Dennis because she had a hysterical pregnancy. The rest of the play stays at the house, even if it includes the kitchen or the backyard, but the trip to the road house, complete with a pair of workers there, strains credulity. This play is set in the early '60s but putting a jukebox and a woody station wagon in it doesn't help, it just limits it. Burton, in his sweater and daddy glasses, just looks out of place. It was a mistake.

The film was nominated for thirteen Oscars. Taylor and Dennis won, Burton and Segal were nominated. Taylor was certainly not everyone's first choice--she was a glamorous movie star, and the role had been played by older, less photogenic women like Uta Hagen and Elaine Stritch. But she was game, braying like a jackass when called for. Burton was more tailor-made for the part, keeping his Royal Academy accent, sounding just like an ineffectual history professor. When the play is done right, it's the character of George who "wins" the evening, and I'm not sure Burton does that here.Taylor was the bigger star and she gets the lion's share of attention.

Nichols does film the interiors in the house masterfully. There are many, many close-ups, two-shots, and intriguing three-shots--I can't imagine how many set-ups there were. Often the actors are photographed from below, making them look like monsters. especially George and Martha. It was shot in black and white, by Haskell Wexler (he won an Oscar, the last for Black-and-White Cinematography, by then it was old hat) and has the proper boozy, smoke-filled feeling. The opening shot is of a full moon, as if it were a Universal Wolf Man picture, and then we see that moon again, just before the last act, which Albee called "Walpurgisnacht."

While the film version is not up to the stage version, it is still a monumental achievement, and Albee, who was kind of embarrassed by the attention he got for it, certainly probably appreciated the money it generated, still captures the essence of the play, as described by Martha: "George, my husband... George, who is out somewhere there in the dark, who is good to me - whom I revile, who can keep learning the games we play as quickly as I can change them. Who can make me happy and I do not wish to be happy. Yes, I do wish to be happy. George and Martha: Sad, sad, sad. Whom I will not forgive for having come to rest; for having seen me and having said: yes, this will do."

As I mentioned in my review of the revival on Broadway a few years ago, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf is my favorite play. Albee, following the death of Eugene O'Neill and the kind of petering out of Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller, assumed the mantle of America's playwright. Ben Brantley in the Times think he held it until Tony Kushner's Angels in America, but I might stick up for Sam Shepard. In any event, Albee was a giant of American dramatists, and Virginia Woolf was his masterpiece.

It was a sensation on Broadway, both hated and worshiped, and was made into a film by Mike Nichols. It was Nichols' first film, after an amazing run on Broadway that saw five of his plays running at the same time. But mostly he did Neil Simon and other light fare. Virginia Woolf was as dark as a moonless night. He was also working with, at the time, the most famous people in the world, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton.

The film version is very, very good, but shows the pitfalls of taking a play that is perfect as it is and trying to adapt it for cinema. The play takes one in one living room in almost real time. Some films that are adapted for films that don't "break out" are often called "stagey," because cinema is supposed to be expansive. Who decided this, I don't know. So what Nichols did is very daring. He did break out, but the script, written by producer Ernest Lehman, adds almost nothing. Albee joked that he added one line and was paid a million dollars. What Lehman and Nichols did was try to turn it into a movie.

To those who are too young or too isolated to know the story, it is about four people who are like scorpions in a bottle. George and Martha, probably not coincidently named for the father and mother of our country, are Burton and Taylor. He's an ineffectual, intellectual history professor, she's the blousy daughter of the president of the college (in the play she's older than George, but I suppose no one would believe Taylor was older than Burton). They have returned from a faculty party, and bicker as if it were second nature (she wants to know where the line "What a dump!" comes from. It is never answered, but for trivia buffs it is Bette Davis in Beyond the Forest). It is two in the morning, but Taylor has invited a young faculty member, George Segal, and his wife, Sandy Dennis, over for a nightcap. Thus begin the games.

What follows is some of the most bilious dialogue ever written for the American stage, or for the American screen. Burton and Taylor have something of an understanding in their marriage--they constantly fight--"If you existed I'd divorce you," Taylor tells him, but Segal and Dennis don't quite understand it. Segal, whom Taylor pointedly seduces, is a biologist, whom Burton mistrusts--he's convinced biology will make everyone the same, and end all creativity--ooks askance at the sideshow he's watching. Dennis quickly gets drunk on brandy, and is mocked for her "slim hips" and being a "simp." When she later twirls herself around in a road house, shouting "I dance like the wind," or claps shouting "Violence! Violence!" you both feel sorry for her and hate her.

There's a point you hate everyone in this play, but also feel the deepest empathy. Albee, during his whole career, peeled back the facade, especially of academic and upper-middle-class types. In this play, the skeleteons in the closet are practically dancing--at the center of the play is the supposed son of Burton and Taylor. Though this story is over fifty years old, I choose not to reveal it here.

Nichols and Lehman kept Albee's vitriolic language. It often has the sound of percussion, with the repetition of words like "flop," and "snap!" The insults are often laugh out-loud funny, even when the cut to the bone. Burton says to Taylor: "And please keep your clothes on, too. There aren't many more sickening sights in this world than you with a few drinks in you and your skirt up over your head." They keep the three act structure, with each being a game--"Humiliate the Host," "Get the Guests," ("Hump the Hostess" happens off screen) and then "Bringing Up Baby."

But where the film goes a little off the rails is the scene at the roadhouse. This is where "Get the Guests" is played, where Burton reveals what Segal told him--that he married Dennis because she had a hysterical pregnancy. The rest of the play stays at the house, even if it includes the kitchen or the backyard, but the trip to the road house, complete with a pair of workers there, strains credulity. This play is set in the early '60s but putting a jukebox and a woody station wagon in it doesn't help, it just limits it. Burton, in his sweater and daddy glasses, just looks out of place. It was a mistake.

The film was nominated for thirteen Oscars. Taylor and Dennis won, Burton and Segal were nominated. Taylor was certainly not everyone's first choice--she was a glamorous movie star, and the role had been played by older, less photogenic women like Uta Hagen and Elaine Stritch. But she was game, braying like a jackass when called for. Burton was more tailor-made for the part, keeping his Royal Academy accent, sounding just like an ineffectual history professor. When the play is done right, it's the character of George who "wins" the evening, and I'm not sure Burton does that here.Taylor was the bigger star and she gets the lion's share of attention.

Nichols does film the interiors in the house masterfully. There are many, many close-ups, two-shots, and intriguing three-shots--I can't imagine how many set-ups there were. Often the actors are photographed from below, making them look like monsters. especially George and Martha. It was shot in black and white, by Haskell Wexler (he won an Oscar, the last for Black-and-White Cinematography, by then it was old hat) and has the proper boozy, smoke-filled feeling. The opening shot is of a full moon, as if it were a Universal Wolf Man picture, and then we see that moon again, just before the last act, which Albee called "Walpurgisnacht."

While the film version is not up to the stage version, it is still a monumental achievement, and Albee, who was kind of embarrassed by the attention he got for it, certainly probably appreciated the money it generated, still captures the essence of the play, as described by Martha: "George, my husband... George, who is out somewhere there in the dark, who is good to me - whom I revile, who can keep learning the games we play as quickly as I can change them. Who can make me happy and I do not wish to be happy. Yes, I do wish to be happy. George and Martha: Sad, sad, sad. Whom I will not forgive for having come to rest; for having seen me and having said: yes, this will do."

Comments

Post a Comment