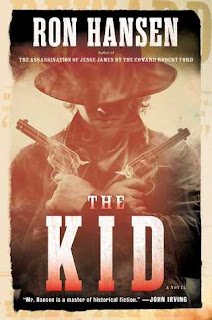

The Kid

There has been so much written about Billy the Kid, fiction and fact, that Ron Hansen's novel of last year doesn't seem at first to be necessary. But, along with Mary Doria Russell's Epitaph, there seems to be a trend lately to write historical fiction that is close to accurate, and that The Kid is. For Western fans, there's not much new here, but it was a pleasure to read.

One of the things I enjoy about Westerns, both in print and on film, is the style of putting grandiloquent language in cowpoke's mouths. You can see this done to death on Deadwood, but apparently these guys had some education, and the education they had was formal. Therefore you get dialogue like “I deserve whatever you hand out in regard to admonishment,” he said. “I done wrong and judge myself kindly in need of correction.”

That statement was by Pat Garrett, the lawman who hunted down Billy, but the Kid himself, who was known by many names--William Bonney, Henry Antrim (that was his stepfather's name) or just Billy the Kid, is a regular cut-up. He's asked for a bit of advice and answers,“Well,” the Kid said, “I would advise your readers to never engage in killing.”

In fact, Billy was a horse thief who got caught up in what was known as the Lincoln County War, a turf struggle between ranchers in New Mexico in the late 1870s. Billy, who stole a man named John Tunstall's horse, was hired by him, and later rode with men who sought vengeance for Tunstall's murder. Billy was nothing if not loyal. His loyalty to the family of his sweetheart, Paulita, would prove to be his undoing. Hansen admires the Kid, who only claimed to have killed two people (he would later kill two more in his celebrated jail break, when he killed a rascal named Bob Olinger with a blast to the face, before which he said, "Hello, Bob") was the stuff of dime novels. Only in his late teens when he perpetrated most of what he was supposed to have done, he had only one picture of him taken in his lifetime, and was by all accounts charming.

The Kid made the front page of the Chicago Daily Tribune on December 29, when it named “Billy the Kid” as the leader of “the notorious gang of outlaws composed of about 25 men who have for the past six months overrun Eastern New Mexico, murdering and committing other deeds of outlawry.” He was quick with a gun but was blamed for every death that happened while he was nearby. Therefore he became Moby Dick to Garrett's Ahab. After he broke out of jail, Garrett says, "I’ll follow the Kid to the end of time, and there will be a fierce reckoning. There will be a whirlwind he will reap while desperately begging for my forgiveness.”

When Billy broke out of his jail he was advised to go to Mexico, but instead went to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, where Paulita Maxwell lived. He was disheartened to find out she was going to marry another man. Garrett went looking for him there, and when Billy went to the father's bedroom, asking in Spanish, "Who is it?" Garrett shot him in the heart, in pitch darkness. He was 21.

The Kid's reputation was revived by a book full of alternative facts by Walter Noble Burns in the 1920s, and then came many film adaptations.“The boy who never grew old,” Burns wrote, “has become a sort of symbol of frontier knight-errantry, a figure of eternal youth riding forever through a purple glamour of romance.”

Hansen, who also wrote of another Western legend in The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, writes with a nice, blood and thunder style. I particularly liked the way he sent off characters who would not appear again in the book, telling us what became of them: "Sombrero Jack, by then, had heard of the Kid’s arrest and skinned his way out of town and out of this narrative, but he would find Jesus and finally reform his life and wind up a justice of the peace in Colorado."

At times the telling of the Lincoln County War is very complicated, as there are many names to keep track of (Hansen says in the acknowledgements that he actually removed some characters!) but it's best to read this book not as a history but as a good oater that actually was true. It seems that if there were no Billy the Kid we'd have to invent him.

One of the things I enjoy about Westerns, both in print and on film, is the style of putting grandiloquent language in cowpoke's mouths. You can see this done to death on Deadwood, but apparently these guys had some education, and the education they had was formal. Therefore you get dialogue like “I deserve whatever you hand out in regard to admonishment,” he said. “I done wrong and judge myself kindly in need of correction.”

That statement was by Pat Garrett, the lawman who hunted down Billy, but the Kid himself, who was known by many names--William Bonney, Henry Antrim (that was his stepfather's name) or just Billy the Kid, is a regular cut-up. He's asked for a bit of advice and answers,“Well,” the Kid said, “I would advise your readers to never engage in killing.”

In fact, Billy was a horse thief who got caught up in what was known as the Lincoln County War, a turf struggle between ranchers in New Mexico in the late 1870s. Billy, who stole a man named John Tunstall's horse, was hired by him, and later rode with men who sought vengeance for Tunstall's murder. Billy was nothing if not loyal. His loyalty to the family of his sweetheart, Paulita, would prove to be his undoing. Hansen admires the Kid, who only claimed to have killed two people (he would later kill two more in his celebrated jail break, when he killed a rascal named Bob Olinger with a blast to the face, before which he said, "Hello, Bob") was the stuff of dime novels. Only in his late teens when he perpetrated most of what he was supposed to have done, he had only one picture of him taken in his lifetime, and was by all accounts charming.

The Kid made the front page of the Chicago Daily Tribune on December 29, when it named “Billy the Kid” as the leader of “the notorious gang of outlaws composed of about 25 men who have for the past six months overrun Eastern New Mexico, murdering and committing other deeds of outlawry.” He was quick with a gun but was blamed for every death that happened while he was nearby. Therefore he became Moby Dick to Garrett's Ahab. After he broke out of jail, Garrett says, "I’ll follow the Kid to the end of time, and there will be a fierce reckoning. There will be a whirlwind he will reap while desperately begging for my forgiveness.”

When Billy broke out of his jail he was advised to go to Mexico, but instead went to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, where Paulita Maxwell lived. He was disheartened to find out she was going to marry another man. Garrett went looking for him there, and when Billy went to the father's bedroom, asking in Spanish, "Who is it?" Garrett shot him in the heart, in pitch darkness. He was 21.

The Kid's reputation was revived by a book full of alternative facts by Walter Noble Burns in the 1920s, and then came many film adaptations.“The boy who never grew old,” Burns wrote, “has become a sort of symbol of frontier knight-errantry, a figure of eternal youth riding forever through a purple glamour of romance.”

Hansen, who also wrote of another Western legend in The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, writes with a nice, blood and thunder style. I particularly liked the way he sent off characters who would not appear again in the book, telling us what became of them: "Sombrero Jack, by then, had heard of the Kid’s arrest and skinned his way out of town and out of this narrative, but he would find Jesus and finally reform his life and wind up a justice of the peace in Colorado."

At times the telling of the Lincoln County War is very complicated, as there are many names to keep track of (Hansen says in the acknowledgements that he actually removed some characters!) but it's best to read this book not as a history but as a good oater that actually was true. It seems that if there were no Billy the Kid we'd have to invent him.

Comments

Post a Comment