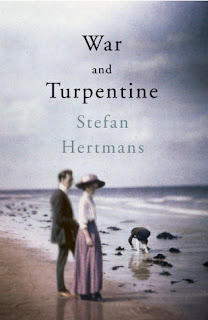

War and Turpentine

"This paradox was the constant in his life, as he was tossed back and forth between the soldier he had to be and the artist he’d wished to become. War and turpentine." So writes Stefan Hertmans in his novel, War and Turpentine, which is narrated by a man writing about his grandfather. The grandfather fought in World War I, and left a memoir for his grandson to read. After delaying reading it, he finally does, and that allows the grandson to remember all sorts of things about the old man.

The grandfather's name is Urbain Martiens, born in Ghent. His father was a painter of frescoes, but died young. Urbain becomes an artist, but only an amateur one, but it was a major part of his life. He is a realist, disdainful of "daubers" like Van Gogh and Gaugin. "They’re all daubers, today’s painters; they’ve completely lost touch with the classical tradition, the subtle, noble craft of the old masters. They muddle along with no respect for the laws of anatomy, don’t even know how to glaze, never mix their own paint, use turpentine like water, and are ignorant of the secrets of grinding your own pigments, of fine linseed oil and the blowing of siccatives—no wonder there are no more great painters."

Urbain as an old man is a proper man, who wears a jacket and tie to the beach. He was in passionate love with a woman who died of the Spanish flu; he married her sister, and while he they were affectionate it was not a marriage of passion. They had one daughter, the mother of our narrator.

The center of the book is Urbain's war-time experiences. This is brutal stuff--he is wounded three times. Hertmans excels at bringing the misery to life through Urbain's writings, as he writes about men who committed suicide by charging the Germans from their trenches--a quick death was preferable to the living conditions.

I enjoyed this book, as it beautifully written, but I was never fully engaged. The war stuff is top-drawer, but some of the rumination by the narrator is uninteresting. The last part of the book, when the narrator visits some of the battle sites where his grandfather fought, are very moving, though.

I guess the two words of the title are never brought together satisfactorily. I did admire one passage, and wonder if all artists who go to war think this way: "Between the villages, the countryside was stunning. Summer clouds drifted over the waving grain in the distance, the stands of trees in the pastures shaded the grazing cattle, swallows and larks darted through the air, sticklebacks glinted in the clear brooks, lines of willows swayed their branches in the warm breeze. It reminded

me of the seventeenth-century Dutch landscape painters, of their peaceful pictures, of treetops painted by the English artist Constable, dappled with patches of light and shadow, of the tranquil existence he had captured on canvas."

The grandfather's name is Urbain Martiens, born in Ghent. His father was a painter of frescoes, but died young. Urbain becomes an artist, but only an amateur one, but it was a major part of his life. He is a realist, disdainful of "daubers" like Van Gogh and Gaugin. "They’re all daubers, today’s painters; they’ve completely lost touch with the classical tradition, the subtle, noble craft of the old masters. They muddle along with no respect for the laws of anatomy, don’t even know how to glaze, never mix their own paint, use turpentine like water, and are ignorant of the secrets of grinding your own pigments, of fine linseed oil and the blowing of siccatives—no wonder there are no more great painters."

Urbain as an old man is a proper man, who wears a jacket and tie to the beach. He was in passionate love with a woman who died of the Spanish flu; he married her sister, and while he they were affectionate it was not a marriage of passion. They had one daughter, the mother of our narrator.

The center of the book is Urbain's war-time experiences. This is brutal stuff--he is wounded three times. Hertmans excels at bringing the misery to life through Urbain's writings, as he writes about men who committed suicide by charging the Germans from their trenches--a quick death was preferable to the living conditions.

I enjoyed this book, as it beautifully written, but I was never fully engaged. The war stuff is top-drawer, but some of the rumination by the narrator is uninteresting. The last part of the book, when the narrator visits some of the battle sites where his grandfather fought, are very moving, though.

I guess the two words of the title are never brought together satisfactorily. I did admire one passage, and wonder if all artists who go to war think this way: "Between the villages, the countryside was stunning. Summer clouds drifted over the waving grain in the distance, the stands of trees in the pastures shaded the grazing cattle, swallows and larks darted through the air, sticklebacks glinted in the clear brooks, lines of willows swayed their branches in the warm breeze. It reminded

me of the seventeenth-century Dutch landscape painters, of their peaceful pictures, of treetops painted by the English artist Constable, dappled with patches of light and shadow, of the tranquil existence he had captured on canvas."

Comments

Post a Comment