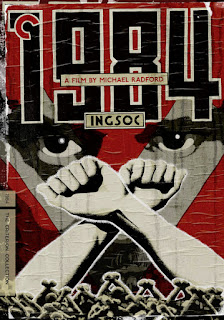

Nineteen Eighty-Four

There were three adaptations of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four in the '50s, starring actors as diverse as Eddie Albert, Peter Cushing, and Edmond O'Brien. In November 1983 a young director, Michael Radford, who had only one feature under his belt, thought that a film should be made for the year of the title. He found out who had the rights, a lawyer in Chicago, and banged out a script in three weeks. He got his ideal actor to play Winston Smith, John Hurt, and the film was released in 1984 in the U.K. (it didn't come to the U.S. until February 1985). After all that, Radford made the definitive version of the novel.

The novel is familiar to many--a common man, Smith, is seduced into rebellion by both his own intellect and a woman (Suzanna Hamilton), who brings him hope. But the party of his nation of Oceania, through the use of surveillance and "thought police," capture him. He is brainwashed by a party official, O'Brien (played by Richard Burton in his last screen role) and ultimately broken by his worst fear into betraying his love.

Radford takes the right approach on almost everything. The film looks like the science-fiction of when Orwell wrote it, 1948, so there are telescreens, but also rotary phones and pneumatic tubes. The overall look is London after the war, with crumbling buildings and garbage in the streets, as well as a touch of the Soviet, with bland, concrete architecture. The party, INGSOC, keep the people under thumb and utilizes psychological methods to keep them that way, such as creating a straw man, Emmanuel Goldstein, for them to hate, and constantly blasting propaganda over the airwaves (they can't turn off their telescreens).

The great Roger Deakins was the cinematographer (it was only his second film as well) and while the film is not in black and white, it was washed out enough to make colors pop, such as the red sash around Hamilton's waste (everyone in this society wears jumpsuits, color coded). The Ministry of Love, where the second half of the film takes place, is banal, and Room 101, where Hurt is presented with his ultimate fear, rats, is plain (Deakins reveals that they just made it a dark room because they had no budget).

Hurt is perfect as Smith--he always looked as if he had tuberculosis, and Smith is described as frail, and Hamilton, who sadly didn't do much after this, is almost impressive, especially as in many of her scenes she is buck naked. Burton, who ended up with the role after it was turned down by Paul Scofield, Alan Bates, and Marlon Brando, was said to have enjoyed himself immensely. He tortures Hurt and speaks to him in almost comforting tones. The way he describes the savagery of the rats is chilling. No one had a voice like his.

There haven't been any more adaptations of the book since then, and that is good, because I don't think this one can be surpassed. The book, and the film, are always relevant--the gatherings in Victory Square look a lot like a Trump rally--and Radford's adaptation can be viewed again and again, just as the book can be read again and again.

The novel is familiar to many--a common man, Smith, is seduced into rebellion by both his own intellect and a woman (Suzanna Hamilton), who brings him hope. But the party of his nation of Oceania, through the use of surveillance and "thought police," capture him. He is brainwashed by a party official, O'Brien (played by Richard Burton in his last screen role) and ultimately broken by his worst fear into betraying his love.

Radford takes the right approach on almost everything. The film looks like the science-fiction of when Orwell wrote it, 1948, so there are telescreens, but also rotary phones and pneumatic tubes. The overall look is London after the war, with crumbling buildings and garbage in the streets, as well as a touch of the Soviet, with bland, concrete architecture. The party, INGSOC, keep the people under thumb and utilizes psychological methods to keep them that way, such as creating a straw man, Emmanuel Goldstein, for them to hate, and constantly blasting propaganda over the airwaves (they can't turn off their telescreens).

The great Roger Deakins was the cinematographer (it was only his second film as well) and while the film is not in black and white, it was washed out enough to make colors pop, such as the red sash around Hamilton's waste (everyone in this society wears jumpsuits, color coded). The Ministry of Love, where the second half of the film takes place, is banal, and Room 101, where Hurt is presented with his ultimate fear, rats, is plain (Deakins reveals that they just made it a dark room because they had no budget).

Hurt is perfect as Smith--he always looked as if he had tuberculosis, and Smith is described as frail, and Hamilton, who sadly didn't do much after this, is almost impressive, especially as in many of her scenes she is buck naked. Burton, who ended up with the role after it was turned down by Paul Scofield, Alan Bates, and Marlon Brando, was said to have enjoyed himself immensely. He tortures Hurt and speaks to him in almost comforting tones. The way he describes the savagery of the rats is chilling. No one had a voice like his.

There haven't been any more adaptations of the book since then, and that is good, because I don't think this one can be surpassed. The book, and the film, are always relevant--the gatherings in Victory Square look a lot like a Trump rally--and Radford's adaptation can be viewed again and again, just as the book can be read again and again.

Comments

Post a Comment