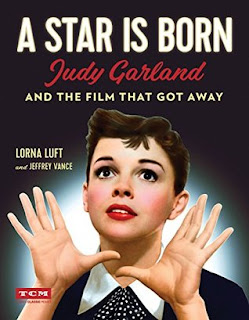

A Star Is Born: Judy Garland And The Film That Got Away

"This book tells the compelling story of the making of A Star Is Born, the film that was to be Garland’s crowning achievement but instead—and undeservedly—marked the end of her great career as a motion picture star." That's at the beginning of A Star Is Born, subtitled Judy Garland And The Film That Got Away, written by Garland's daughter, Lorna Luft, and film historian Jeffrey Vance. It certainly fulfills that statement as Vance writes about the other versions of the story, and Luft handles the film her mother made. I'm always weary of things written by people who are too close to the subject, but Luft, despite referring to Garland as "Mama," and while telling us often of Garland's great talent, doesn't hide the warts.

"Garland, a former top star of unmatched talent, also brought a lot of baggage onto the studio lot: a fragile constitution, dependency on prescription medication, habits of lateness and volatility, and unmanaged manic depression." She had lost her MGM contract in the late '40s, and this vehicle, the first remake of William Wellman's 1937 film of the same name, produced by her husband, Sid Luft, was to be her comeback, and it almost was.

The first chapter is fascinating, as Vance takes us through the Wellman film, which I was surprised to learn was based on a 1932 film, What Price, Hollywood? that was directed by none other than George Cukor, who would direct the Garland film. But is was dogged by going over budget--at $600,000 it was the most expensive film made up until that time. But the bigger problem was the film's length--181 minutes, the longest film since Gone With The Wind, and the longest ever made by Warner Brothers.

Despite the fact that GWTW was the highest grossing picture at that time, and that the uncut version drew large crowds and smash reviews, Harry Warner wanted it cut. Partly that was due to theater owners demanding a shorter film so they could have more screenings per day, but also because Harry wanted to interfere in what was his brother Jack's domain. It was a disaster. Once the cut version was out there, audiences stayed away and critics hated it. Luft says that even projectionists made their own cuts, something she rightly says would never happen to a Spielberg film.

The film still had Oscar nominations, including for Garland and co-star James Mason. Garland had just given birth to her son Joey, so film crews were in her hospital room in case she had won. But she didn't. In a huge upset Grace Kelly won for The Country Girl. Much of Luft's writing about this comes off as sour grapes. She says that Kelly had only been making films for four years, Garland obviously much longer. The Oscars have a long history of passing over stars who are due (ask Glenn Close about it). But many were outraged. Groucho Marx sent her a telegram stating "This is the biggest robbery since Brinks."

Vance then details the 1976 Barbra Streisand version (which I have not seen) which made the female character a feminist (the1954 Garland version ends with her saying, "I am Mrs. Norman Maine," not exactly a feminist manifesto. Then we get a chapter on the reconstruction of the film in 1983. Researchers found a complete audio track, and all but twenty minutes of visual, so they used still photographs instead. When you watch the film on home media, you are seeing the uncut version. Luft adds that after the premiere of the restoration at Radio City Music Hall, she and her sister, Liza Minelli, sobbed for twenty minutes in a backroom of the theater.

Anyone who loves this film, or Garland (Luft offers a basic biography, before and after the film, even her reinterment from a cemetery in Hartsdale, New York to Hollywood Forever, a cemetery that encourages visitors) or is just interested in a backstage peep at the making of a Hollywood classic, would enjoy this book. I certainly did.

Comments

Post a Comment