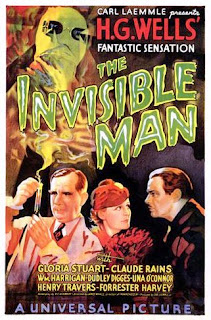

The Invisible Man (1933)

H.G. Wells' novel The Invisible Man was published in 1897, but it wasn't until 1933 that it was turned into a film. There were "invisible man" movies made in the silent days, by Georges Melies, among others. But the special effects hadn't been perfect enough until John P. Fulton perfected a matte process that enabled the "invisible man" to be shown partially clothed.

The film was directed by James Whale, who had made a sensation with Frankenstein in 1931. This film, which would launch a series of films in the Universal horror pantheon, followed some of the same structure as that earlier film--a scientist, mad with power, has gone off and done something amazing, but at the same time alienates his fiancee and terrorizes a community, with his creation ultimately destroying him.

After a dozen or so writers made treatments of the material, including John Huston and Preston Sturges, the eventual writer, R.C. Sheriff, stuck pretty closely to Wells' story (a good idea--the novelist had final script approval). The opening scene is exactly the same as in the novel--a stranger makes his way through a snowstorm to an inn in a small town. The first shot of his face, framed in a doorway, is done precisely the same way Whale did it in the first closeup of the monster in Frankenstein--three shots, each progressively closer.

The stranger, garbed head to toe, his face covered in bandages, excites the customers of the inn, but when he gets violent with the hosts he reveals his secret, and goes into hiding. The major difference between the book and film is that Sheriff has given Griffin a girl--Gloria Stuart (who would one day be in Titanic), the daughter of his mentor (played by Henry Travers, best known as Clarence in It's a Wonderful Life). His rival for Stuart and his colleague, Kemp (William Harrigan) is not heroic as he was in the book, but instead is a sniveling coward. Griffin attempts to make Kemp his partner, and reveals his plan of ruling the world.

Because Griffin has a woman, he shows more humanity than he does in the book, but he also shows much more megalomania. In the book, I believe he kills one person, but in the film it's hundreds, most notably by derailing a train. Kemp comes to an untimely and sardonic end, bound inside a car as it plummets off a cliff.

In the film, the invisibility is created with the use of monocaine, which Travers describes as a "terrible drug." After all, there isn't time in a 71-minute movie to go into all the discussion of optics and light refraction that the book does. The side effect is that it makes its user crazy, and Griffin really goes off the deep end, at one point dancing down a lane wearing only a pair of trousers, singing "Here We Go Gathering Nuts in May."

The film was a big hit, and Whale would have a few years of creative control at Universal. The film has many of his familiar touches, most notably a black sense of humor and a use of what is commonly known as "camp," which is often found in gay culture. For example, one of Whale's favorite actresses was Una O'Connor, who here plays the mistress of the inn. She is given to goggle-eyed over acting, and has at least three scenes where she is called upon to shriek like a banshee.

Griffin was played by Claude Rains, in his first American film. Of course, he isn't seen until the last shot, dying in his hospital bed. Boris Karloff was the first choice to play the part, but he left Universal over money. Whale chose Rains because of his smooth, theatrical voice, and he has a great maniacal laugh.

I've seen the film several times and it never fails to charm. The film was marketed as a horror picture, but it often plays like a comedy. I loved little touches like Rains sitting in a chair, in pajamas, crossing his legs, with of course no flesh showing. The most difficult shot was when he takes off his bandages while looking in a mirror. The photography was done by Arthur Edeson--how did I not know that he would later shoot The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca?

If you look quick you can see Walter Brennan and John Carradine in small roles.

The film was directed by James Whale, who had made a sensation with Frankenstein in 1931. This film, which would launch a series of films in the Universal horror pantheon, followed some of the same structure as that earlier film--a scientist, mad with power, has gone off and done something amazing, but at the same time alienates his fiancee and terrorizes a community, with his creation ultimately destroying him.

After a dozen or so writers made treatments of the material, including John Huston and Preston Sturges, the eventual writer, R.C. Sheriff, stuck pretty closely to Wells' story (a good idea--the novelist had final script approval). The opening scene is exactly the same as in the novel--a stranger makes his way through a snowstorm to an inn in a small town. The first shot of his face, framed in a doorway, is done precisely the same way Whale did it in the first closeup of the monster in Frankenstein--three shots, each progressively closer.

The stranger, garbed head to toe, his face covered in bandages, excites the customers of the inn, but when he gets violent with the hosts he reveals his secret, and goes into hiding. The major difference between the book and film is that Sheriff has given Griffin a girl--Gloria Stuart (who would one day be in Titanic), the daughter of his mentor (played by Henry Travers, best known as Clarence in It's a Wonderful Life). His rival for Stuart and his colleague, Kemp (William Harrigan) is not heroic as he was in the book, but instead is a sniveling coward. Griffin attempts to make Kemp his partner, and reveals his plan of ruling the world.

Because Griffin has a woman, he shows more humanity than he does in the book, but he also shows much more megalomania. In the book, I believe he kills one person, but in the film it's hundreds, most notably by derailing a train. Kemp comes to an untimely and sardonic end, bound inside a car as it plummets off a cliff.

In the film, the invisibility is created with the use of monocaine, which Travers describes as a "terrible drug." After all, there isn't time in a 71-minute movie to go into all the discussion of optics and light refraction that the book does. The side effect is that it makes its user crazy, and Griffin really goes off the deep end, at one point dancing down a lane wearing only a pair of trousers, singing "Here We Go Gathering Nuts in May."

The film was a big hit, and Whale would have a few years of creative control at Universal. The film has many of his familiar touches, most notably a black sense of humor and a use of what is commonly known as "camp," which is often found in gay culture. For example, one of Whale's favorite actresses was Una O'Connor, who here plays the mistress of the inn. She is given to goggle-eyed over acting, and has at least three scenes where she is called upon to shriek like a banshee.

Griffin was played by Claude Rains, in his first American film. Of course, he isn't seen until the last shot, dying in his hospital bed. Boris Karloff was the first choice to play the part, but he left Universal over money. Whale chose Rains because of his smooth, theatrical voice, and he has a great maniacal laugh.

I've seen the film several times and it never fails to charm. The film was marketed as a horror picture, but it often plays like a comedy. I loved little touches like Rains sitting in a chair, in pajamas, crossing his legs, with of course no flesh showing. The most difficult shot was when he takes off his bandages while looking in a mirror. The photography was done by Arthur Edeson--how did I not know that he would later shoot The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca?

If you look quick you can see Walter Brennan and John Carradine in small roles.

Comments

Post a Comment