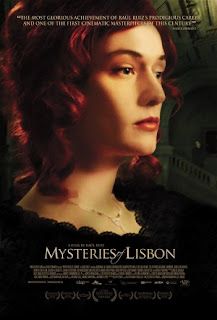

Mysteries of Lisbon

Raul Ruiz's Mysteries of Lisbon was on several end-of-year best lists, and I expected some sort of avant-garde European film, but instead it was sumptuous, old fashioned film based on a nineteenth-century Portuguese novel that recalls the work of Dickens or Eliot. It's a beast--over four hours long, so I watched it in two parts. I found it enjoyable, if a little dry

The story, which takes place in Lisbon and France during what appears to be the early part of the nineteenth century, is an interconnecting web of characters, most of whom center around an orphan living in a church school. The boy is closely watched over by the priest (Adriano Luz), who finally tells the boy about his parentage. This is the first of many flashbacks, which are novelistically rendered: a character sits in a chair and tells the story, while it is acted out for us.

Many characters reappear in the narrative under different identities, especially a hired killer (Ricardo Pireira), who calls himself "knife-eater." He had been hired to kill the boy by the mother's father, who did not wish his daughter's reputation to be ruined. That killer is bought off by Luz while posing as a gypsy. Luz also has two backstories: one, told him to by his father, whom he didn't know was his father, and another about his time in Napoleon's army.

The story is dense, so attention should be paid. I find a few loose ends still dangling, even after nearly four and a half hours. But Ruiz's camera work is exemplary. He frequently makes use of long shots, often through windows, which gives the viewer a sense of being a voyeur. One such shot is extremely playful, as we watch, through the window of a carriage, as one character attempts to shoot another, only for that character to be chased by the man he obviously just missed.

Though there are many coincidences, Ruiz does not employ a sentimental style. One character, who at the beginning of the film is rich, ends up a blind beggar, but no heartstrings are pulled at. Another character, a poor man, simply says, "What is normal for us is notorious tragedy for the nobility."

The story, which takes place in Lisbon and France during what appears to be the early part of the nineteenth century, is an interconnecting web of characters, most of whom center around an orphan living in a church school. The boy is closely watched over by the priest (Adriano Luz), who finally tells the boy about his parentage. This is the first of many flashbacks, which are novelistically rendered: a character sits in a chair and tells the story, while it is acted out for us.

Many characters reappear in the narrative under different identities, especially a hired killer (Ricardo Pireira), who calls himself "knife-eater." He had been hired to kill the boy by the mother's father, who did not wish his daughter's reputation to be ruined. That killer is bought off by Luz while posing as a gypsy. Luz also has two backstories: one, told him to by his father, whom he didn't know was his father, and another about his time in Napoleon's army.

The story is dense, so attention should be paid. I find a few loose ends still dangling, even after nearly four and a half hours. But Ruiz's camera work is exemplary. He frequently makes use of long shots, often through windows, which gives the viewer a sense of being a voyeur. One such shot is extremely playful, as we watch, through the window of a carriage, as one character attempts to shoot another, only for that character to be chased by the man he obviously just missed.

Though there are many coincidences, Ruiz does not employ a sentimental style. One character, who at the beginning of the film is rich, ends up a blind beggar, but no heartstrings are pulled at. Another character, a poor man, simply says, "What is normal for us is notorious tragedy for the nobility."

Comments

Post a Comment