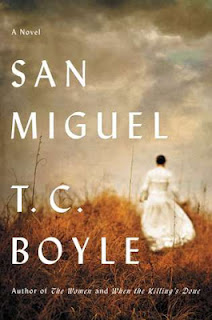

San Miguel

By his own admission, San Miguel, his 14th novel, is T.C. Boyle's "first book-length narrative in the conventional realist mode, sans

irony or postmodernist sleight of hand." It is the very straightforward story of two families, one in the 1880s-90s and another in the 1930s, who soley occupied San Miguel, a small island in the Channel Islands, off the coast of California.

The book is viewed from the aspect of three women. First is Marantha Waters, the wife of a Civil War veteran from the East who has invested his (and her) money in an attempt to raise sheep on the treeless, windswept island. Marantha is tubercular, and the wet weather doesn't help. She is at first game, but increasingly distraught over the rough and lonely conditions. When she catches her husband dallying with the cook, things spiral badly, until her death.

The next section is devoted to her teenage daughter, Edith. In a Dickensian nightmare, she is captive to Waters after her mother's death, being forced to cook and clean, while she longs for a life in San Francisco as an actress.

The final and longest third is devoted to the Lesters, who serve as caretakers of the sheep ranch starting in 1930. Elise, from New York, thought she was doomed to be an old maid, until swept off her feet by Herbie, who whisked her to San Miguel as a grand adventure. He has bouts of depression, though, and after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor they are forced to endure two fresh-faced sailors who are protecting them from invasion, which Herbie finds laughable since he has a large collection of guns, while the sailors have one World War I-issue rifle between them.

San Miguel, as Boyle notes, is told in a completely different style than his usual smart ass prose. It's in the nature of Little House on the Prairie, or O Pioneers! Here, on this little island that is almost impossible to reach (the invention of the airplane and radio made things a little closer) was one the last places to create a kind of mini-utopia. In fact, when Herbie receives epaulets from the government of Haile Selassie, he thinks of himself, vaingloriously, as the King of San Miguel, and welcomes the attention of reporters and a spread in Life magazine.

Boyle is one of my favorite short story writers, but his novels have been problematic for me. This one is no different. In a sense it does play like Little House on the Prairie, as the narrative is interrupted by various incidents--a visit by Japanese fishermen, a few medical emergencies, etc., I found myself wondering what this all means. I suppose it's the American sense of proclaiming one's self lord of one's castle--Herbie hates Roosevelt, and is enraged when government men come to determine the environmental impact of sheep grazing, but as I finished the book I had a disappointing sense of so what?

But Boyle's use of words is as brilliant as ever, and I was able to feel the isolation on the island. I love to read about places difficult to get to, and I would love to visit (it's now a part of the National Park Service). "She was on an island raked with wind, an island fourteen miles square set down in the heaving froth of the Pacific Ocean, and there was nothing on it but the creatures of nature and an immense rolling flock of sheep that were money on the hoof, income, increase, bleating woolly sacks of greenback dollars."

The book is viewed from the aspect of three women. First is Marantha Waters, the wife of a Civil War veteran from the East who has invested his (and her) money in an attempt to raise sheep on the treeless, windswept island. Marantha is tubercular, and the wet weather doesn't help. She is at first game, but increasingly distraught over the rough and lonely conditions. When she catches her husband dallying with the cook, things spiral badly, until her death.

The next section is devoted to her teenage daughter, Edith. In a Dickensian nightmare, she is captive to Waters after her mother's death, being forced to cook and clean, while she longs for a life in San Francisco as an actress.

The final and longest third is devoted to the Lesters, who serve as caretakers of the sheep ranch starting in 1930. Elise, from New York, thought she was doomed to be an old maid, until swept off her feet by Herbie, who whisked her to San Miguel as a grand adventure. He has bouts of depression, though, and after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor they are forced to endure two fresh-faced sailors who are protecting them from invasion, which Herbie finds laughable since he has a large collection of guns, while the sailors have one World War I-issue rifle between them.

San Miguel, as Boyle notes, is told in a completely different style than his usual smart ass prose. It's in the nature of Little House on the Prairie, or O Pioneers! Here, on this little island that is almost impossible to reach (the invention of the airplane and radio made things a little closer) was one the last places to create a kind of mini-utopia. In fact, when Herbie receives epaulets from the government of Haile Selassie, he thinks of himself, vaingloriously, as the King of San Miguel, and welcomes the attention of reporters and a spread in Life magazine.

Boyle is one of my favorite short story writers, but his novels have been problematic for me. This one is no different. In a sense it does play like Little House on the Prairie, as the narrative is interrupted by various incidents--a visit by Japanese fishermen, a few medical emergencies, etc., I found myself wondering what this all means. I suppose it's the American sense of proclaiming one's self lord of one's castle--Herbie hates Roosevelt, and is enraged when government men come to determine the environmental impact of sheep grazing, but as I finished the book I had a disappointing sense of so what?

But Boyle's use of words is as brilliant as ever, and I was able to feel the isolation on the island. I love to read about places difficult to get to, and I would love to visit (it's now a part of the National Park Service). "She was on an island raked with wind, an island fourteen miles square set down in the heaving froth of the Pacific Ocean, and there was nothing on it but the creatures of nature and an immense rolling flock of sheep that were money on the hoof, income, increase, bleating woolly sacks of greenback dollars."

Comments

Post a Comment