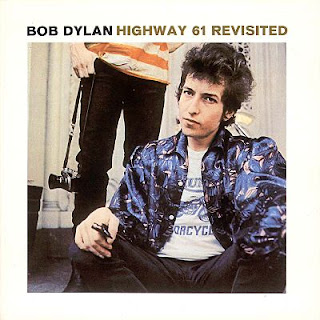

Hghway 61 Revisted

It starts with one beat of a snare drum, then the organ kicks in. "Once upon a time, you drank so fine, You threw the bums a dime in your prime, didn’t you?" So begins one of the most important rock albums of all time, Bob Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited, released fifty years ago this week.

Of course the opening song is "Like a Rolling Stone," one of the greatest of rock songs, and in fact chosen that in many polls. It was a turn of the page in rock history, away from songs of love or political protest, and instead an angry manifesto, an outpouring of cynical rage.

The song is over six minutes long and radio stations balked at playing it, until demand became too great, and now you can hear it almost every hour on a variety of classic rock stations. It was a departure for Dylan--he had written angry songs before, like "Positively Fourth Street"--but this was one was an opus of hostility, a takedown of an unnamed woman who was once on top but is now struggling in a new world:

"You’ve gone to the finest school all right, Miss Lonely

But you know you only used to get juiced in it

And nobody has ever taught you how to live on the street

And now you find out you’re gonna have to get used to it

You said you’d never compromise

With the mystery tramp, but now you realize

He’s not selling any alibis

As you stare into the vacuum of his eyes

And ask him do you want to make a deal?"

Earlier that summer of '65 Dylan went electric, a profound moment in rock and folk music history, losing him fans and gaining him more. Highway 61 Revisited established him as something more than both, like the Beatles, he transcended categories. His poetry, especially, which was a whirligig of words, sounded as if he were speaking another language to some higher born intellect. The best example of this, I think, is in the closing track, "Desolation Row," which is the only song on the album that relies simply on guitar and harmonica:

"Praise be to Nero’s Neptune

The Titanic sails at dawn

And everybody’s shouting

“Which Side Are You On?”

And Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot

Fighting in the captain’s tower

While calypso singers laugh at them

And fishermen hold flowers

Between the windows of the sea

Where lovely mermaids flow

And nobody has to think too much

About Desolation Row"

This is just one of several verses of the song, and I don't know what any of them mean. He drops many names from literature and myth, such as Cinderella, Robin Hood, Einstein, Casanova, the Phantom of the Opera, Ophelia, Cain and Abel, and the Hunchback of Notre Dame. The writing is clearly influenced by Beat poetry, perhaps Allen Ginsberg, and while none of it is specific, taken as a whole it can be thought to be representative of a world gone to Hell--Desolation Row may not be a place as much of a state of civilization.

I think there are two other classics on the record, though all of the songs are fine. The title song, which begins with a slide whistle of all things, starts with the a re-telling of the Abraham and Isaac story:

Oh God said to Abraham,

“Kill me a son”

Abe says, “Man, you must be puttin’ me on”

God say, “No.” Abe say, “What?”

God say, “You can do what you want Abe, but

The next time you see me comin’ you better run”

Well Abe says, “Where do you want this killin’ done?”

God says, “Out on Highway 61”

Highway 61 is that ribbon of road that runs from New Orleans to Dylan's home town of Duluth, Minnesota, and as it wends its way through Mississippi is known for the juke joints and honky tonks along the way, the birthplace of the blues. In each chorus Dylan seems to be telling a story that takes place on that road, a place of sacrifice and renewal.

As great as these songs are, I find the most satisfying to be "Ballad of a Thin Man," maybe because it's the easiest to understand. If you've ever seen the combative press conferences Dylan endured, it's easy to figure that this is an attack on the journalists of the day--"Because something is happening here, but you don't what it is, do you, Mr. Jones?" Todd Haynes made his clear in his film I'm Not There by playing this song during a press conference scene. Dylan's snide laughter in his vocal makes it clear that he disdains the music journalists who were trying to pigeon-hole him, or build a zeitgeist around him:

"You’ve been with the professors

And they’ve all liked your looks

With great lawyers you have

Discussed lepers and crooks

You’ve been through all of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books

You’re very well read

It’s well known"

The other songs on the album are all fine, especially "Queen Jane Approximately," and the rollicking "Tombstone Blues," but the four I've mentioned are the ones that pushed the envelope. Dylan was really the first member of the rock era to so openly declare his cynicism, something that John Lennon and Mick Jagger would later do. Some have written that the '60s really started with the release of this album, as it was the exclamation mark on a long sentence that was questioning authority and the status quo, and was picked up by many other artists.

Of course the opening song is "Like a Rolling Stone," one of the greatest of rock songs, and in fact chosen that in many polls. It was a turn of the page in rock history, away from songs of love or political protest, and instead an angry manifesto, an outpouring of cynical rage.

The song is over six minutes long and radio stations balked at playing it, until demand became too great, and now you can hear it almost every hour on a variety of classic rock stations. It was a departure for Dylan--he had written angry songs before, like "Positively Fourth Street"--but this was one was an opus of hostility, a takedown of an unnamed woman who was once on top but is now struggling in a new world:

"You’ve gone to the finest school all right, Miss Lonely

But you know you only used to get juiced in it

And nobody has ever taught you how to live on the street

And now you find out you’re gonna have to get used to it

You said you’d never compromise

With the mystery tramp, but now you realize

He’s not selling any alibis

As you stare into the vacuum of his eyes

And ask him do you want to make a deal?"

Earlier that summer of '65 Dylan went electric, a profound moment in rock and folk music history, losing him fans and gaining him more. Highway 61 Revisited established him as something more than both, like the Beatles, he transcended categories. His poetry, especially, which was a whirligig of words, sounded as if he were speaking another language to some higher born intellect. The best example of this, I think, is in the closing track, "Desolation Row," which is the only song on the album that relies simply on guitar and harmonica:

"Praise be to Nero’s Neptune

The Titanic sails at dawn

And everybody’s shouting

“Which Side Are You On?”

And Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot

Fighting in the captain’s tower

While calypso singers laugh at them

And fishermen hold flowers

Between the windows of the sea

Where lovely mermaids flow

And nobody has to think too much

About Desolation Row"

This is just one of several verses of the song, and I don't know what any of them mean. He drops many names from literature and myth, such as Cinderella, Robin Hood, Einstein, Casanova, the Phantom of the Opera, Ophelia, Cain and Abel, and the Hunchback of Notre Dame. The writing is clearly influenced by Beat poetry, perhaps Allen Ginsberg, and while none of it is specific, taken as a whole it can be thought to be representative of a world gone to Hell--Desolation Row may not be a place as much of a state of civilization.

I think there are two other classics on the record, though all of the songs are fine. The title song, which begins with a slide whistle of all things, starts with the a re-telling of the Abraham and Isaac story:

Oh God said to Abraham,

“Kill me a son”

Abe says, “Man, you must be puttin’ me on”

God say, “No.” Abe say, “What?”

God say, “You can do what you want Abe, but

The next time you see me comin’ you better run”

Well Abe says, “Where do you want this killin’ done?”

God says, “Out on Highway 61”

Highway 61 is that ribbon of road that runs from New Orleans to Dylan's home town of Duluth, Minnesota, and as it wends its way through Mississippi is known for the juke joints and honky tonks along the way, the birthplace of the blues. In each chorus Dylan seems to be telling a story that takes place on that road, a place of sacrifice and renewal.

As great as these songs are, I find the most satisfying to be "Ballad of a Thin Man," maybe because it's the easiest to understand. If you've ever seen the combative press conferences Dylan endured, it's easy to figure that this is an attack on the journalists of the day--"Because something is happening here, but you don't what it is, do you, Mr. Jones?" Todd Haynes made his clear in his film I'm Not There by playing this song during a press conference scene. Dylan's snide laughter in his vocal makes it clear that he disdains the music journalists who were trying to pigeon-hole him, or build a zeitgeist around him:

"You’ve been with the professors

And they’ve all liked your looks

With great lawyers you have

Discussed lepers and crooks

You’ve been through all of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books

You’re very well read

It’s well known"

The other songs on the album are all fine, especially "Queen Jane Approximately," and the rollicking "Tombstone Blues," but the four I've mentioned are the ones that pushed the envelope. Dylan was really the first member of the rock era to so openly declare his cynicism, something that John Lennon and Mick Jagger would later do. Some have written that the '60s really started with the release of this album, as it was the exclamation mark on a long sentence that was questioning authority and the status quo, and was picked up by many other artists.

Comments

Post a Comment