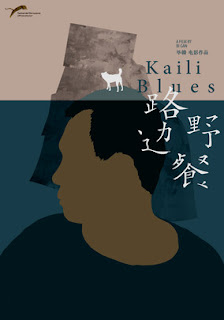

Kaili Blues

Asian directors seem to be in the forefront of making experimental films that disdain the usual Aristotelian notions of time and space, as well as narrative. Some of these films are intriguing and beautiful, and some put me to sleep. Kaili Blues, a 2015 Chinese film by Bi Gan, did both.

The first half concerns a doctor, named Chen, who has been in prison (he came to the aid of a gangster friend who needed revenge). He is working at a clinic and trying to watch over his nephew, Weiwei. The boy's father is called Crazy Face and cares nothing about his son, and eventually sells him. Chen sets out to find him.

About halfway through I was drowsy and had to take a nap, but I stuck with the film. The second half was incomprehensible to me--descriptions I've read say that the village where Chen goes presents his past, present, and future all at the same time, but I didn't get that. Instead I was amazed by what must have been close to a thirty-minute take. The camera follows Chen as he hops on the back of a motorbike and goes to the next town. Then the camera takes a shortcut and meets up with the bike as it comes around a bend. It will go on following characters, such as a woman going across a river in a boat, and will return to Chen in a hair salon. The logistics of his must have been a nightmare. I wonder if Bi Gan got it in one take.

So I really didn't understand this film, but I didn't hate it. It reminded me of the work of Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul, whose films are also inscrutable but somehow strangely beautiful.

Kaili Blues was selected as one of Film Comment's best films of the year by a poll of critics. There are moments when I wonder whether critics select films like these because they think it makes them look smart.

The first half concerns a doctor, named Chen, who has been in prison (he came to the aid of a gangster friend who needed revenge). He is working at a clinic and trying to watch over his nephew, Weiwei. The boy's father is called Crazy Face and cares nothing about his son, and eventually sells him. Chen sets out to find him.

About halfway through I was drowsy and had to take a nap, but I stuck with the film. The second half was incomprehensible to me--descriptions I've read say that the village where Chen goes presents his past, present, and future all at the same time, but I didn't get that. Instead I was amazed by what must have been close to a thirty-minute take. The camera follows Chen as he hops on the back of a motorbike and goes to the next town. Then the camera takes a shortcut and meets up with the bike as it comes around a bend. It will go on following characters, such as a woman going across a river in a boat, and will return to Chen in a hair salon. The logistics of his must have been a nightmare. I wonder if Bi Gan got it in one take.

So I really didn't understand this film, but I didn't hate it. It reminded me of the work of Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul, whose films are also inscrutable but somehow strangely beautiful.

Kaili Blues was selected as one of Film Comment's best films of the year by a poll of critics. There are moments when I wonder whether critics select films like these because they think it makes them look smart.

Comments

Post a Comment