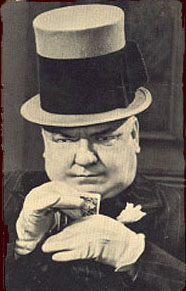

W.C. Fields

To someone of my generation, if W.C. Fields is mentioned, one thinks of an advertising gimmick for corn chips. To someone younger, the response may be a blank stare. Unlike other comedy film giants of the early sound era, Fields is somewhat forgotten. At least his films are, perhaps his persona still looms large.

Unlike the Marx Brothers or Laurel and Hardy or certainly the Three Stooges, Fields movies didn't play much on television. I Netflixed the features that are available on DVD: It's a Gift, International House, You Can't Cheat an Honest Man, My Little Chickadee and The Bank Dick. They are a mixed bag, quality-wise, but Fields strength as a performer shines through. But his image, unlike the other comedians of the period, was not warm and cuddly. The characters he played were inevitably irascible drunkards. Unlike, say, Laurel and Hardy, he did not play people you wanted to cozy up to.

In International House, a curious concoction that comes across like a Vaudeville version of Grand Hotel, complete with performances by Burns and Allen and Cab Calloway, Fields plays a force of nature, an aviator who crash lands into a Chinese hotel. He's all id, lusting for either booze or broads, and whenever he's on screen (he doesn't appear until half-way through) he's magnetic. In You Can't Cheat an Honest Man he is a crooked circus operator, but really functions as comic relief behind the romantic story involving Edgar Bergen (!?)

My Little Chickadee is a clunker. In one of those casting hook-ups that sounds good on paper but don't pan out, Fields is teamed with Mae West. Reports were that they did not get along (West wrote most of the script, and hated the way Fields improvised. She also deplored his drinking). The result is a soggy, unfunny dud.

His best films are probably It's a Gift and The Bank Dick. In both of these films Fields is a hen-pecked husband who wants nothing more than a drink and to sit in the sun. It's a Gift has more laughs, with great set-pieces involving a blind man near a table full of light bulbs and Fields trying to get some sleep on his porch. It is in this film that he comes closest to being lovable, but it does have his signature bit: When challenged by one of his children that he doesn't love them, he cocks his fist and says, "Of course I love you!"

In the documentary as part of the Fields collection, a family friend says that he was funnier off screen than on, and that's easy to believe, as his films, at least his features (he made several shorts) are shambling and have stretches where not much happens. Compared to the diagrammed lunacy of the Marx Brothers, Fields comes up short. However, he certainly deserves to be remembered more than just a pitchman for Fritos.

Comments

Post a Comment