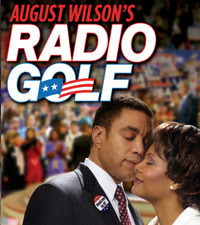

Radio Golf

The extraordinary Radio Golf is August Wilson's last play in his epic, ten-cycle dramatic examination of the African-American experience in the United States during the twentieth century. Wilson died much too young of cancer, but we can be thankful that he had time to finish one of the greatest outputs in contemporary drama.

The extraordinary Radio Golf is August Wilson's last play in his epic, ten-cycle dramatic examination of the African-American experience in the United States during the twentieth century. Wilson died much too young of cancer, but we can be thankful that he had time to finish one of the greatest outputs in contemporary drama.Nine of the plays in Wilson's decalogue (one for each decade) is set in the Hill district of Pittsburgh. Radio Golf concerns the 1990's, when gentrification was in full swing, tearing down the old neighborhoods, that had become swarmed with crime and poverty, and attempting to lure young professionals back.

The main character is Harmond Wilks, played by Harry Lennix, a developer who has plans to run for mayor. He and his partner have bought up a large chunk of land and are putting in an apartment complex and retail area, complete with a Starbucks and a Barnes and Noble. Wilks' wife, played by Tonya Pinkins, is his campaign manager, an ambitious woman who is line for a job with the governor. Things are looking great for all of them.

But then an old man is seen painting one of the houses that are scheduled for demolition. He says it's his house, though it was sold out from under him for tax delinquency. Out of simple decency, Wilks looks into the matter, and finds that the sale was illegal, and that his company really doesn't own the house. He then has to struggle to do what's right.

The play positively crackles with energy and ideas. Golf is a something of a metaphor through the piece. The setting of the play is the construction office, and pinned to the wall are two posters: one of Marting Luther King, Jr., and one of Tiger Woods, and each poster is about the same size. In the program is an article about the history of African-Americans in the golf game, and I was surprised but not shocked to read that the PGA didn't except people of "non-European" heritage until 1961, fourteen years after major league baseball was integrated. Wilks' partner, Roosevelt Hicks, well-played by James A. Williams, is a nut for golf, and it's easy to see that he doesn't just love the game for the game itself, but also for what it signifies: he can play the game of white privilege.

The presence of the old man, Old Joe, brilliantly essayed by Anthony Chisholm, shows a conflict of generations. Old Joe tells Wilks that they'll never let him be mayor. A man born in 1918 still has the emotional scars of prejudice, and has never allowed himself to get caught up in the go-go, new era for black entrepreneur's. But Wilks and Hicks are men of means, and see a place at the table and want to sit down. But Wilks is a man of conscience, and his struggle to do the right thing is electrifying to watch. Lennix's resemblance to Barack Obama adds an unexpected bit of relevance to the proceedings.

The only part of the play I didn't quite buy was the relationship between Wilks and his wife. Although both roles are well acted, it was difficult to see the abiding attraction, even though Wilks has a speech about he met her. Her callous dismissal of his wish to give Old Joe justice was so harsh that it was hard to imagine how they had gotten along this long.

Still, this is a brilliant work, expertly directed by Kenny Leon. It is the perfect capper to Wilson's magnificent cycle.

Comments

Post a Comment