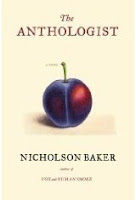

The Anthologist

The Anthologist is the third novel I've read by Nicholson Baker, but the first that wasn't giddily pornographic. Vox was the transcript of a phone-sex conversation, and The Fermata was about a man who could stop time and mostly utilized it to enact his kinky fantasies. The Anthologist has no sex, but it's hero is a distant cousin of the The Fermata's--he's a man obsessed, but in his case it's with poetry. Poetry that rhymes.

The Anthologist is the third novel I've read by Nicholson Baker, but the first that wasn't giddily pornographic. Vox was the transcript of a phone-sex conversation, and The Fermata was about a man who could stop time and mostly utilized it to enact his kinky fantasies. The Anthologist has no sex, but it's hero is a distant cousin of the The Fermata's--he's a man obsessed, but in his case it's with poetry. Poetry that rhymes.Paul Chowder, our narrator, is a poet of minor distinction who lives in Portsmouth, New Hampshire and is working on an anthology of poems that rhyme. He is struggling to write the introduction, and does almost anything to avoid the task, even to the point that his girlfriend Roz leaves him. In the meantime he battles wits with a mouse in his kitchen, goes blueberry picking, buys a new broom, gives a reading at a bookstore, and goes to a conference in Switzerland. But it's what is in-between that gives this book its pleasant bounce.

I'm something of a poetry numbskull. It's one of those things, like jazz, that I think I should like but somehow can't wrap my mind around. Baker, through the voice of Chowder, gives me an indication of why. Poetry, it turns out, is very mathematical (like music). We get an extended lecture on the meter of poetry, of how most great rhyming poetry is in four beats (iambic pentameter is not really the basic rhythm of English poetry), how important rests are, and what enjambing is. The book also could have been subtitled The Secret Lives of Poets, as Chowder relates all sorts of gossipy stories about them, mostly their miserable personal lives (lots of suicides--Lindsay did himself in by drinking Lysol).

I got a big kick out of this book, even though, as I said, poetry goes right over my head. When I try to read it my eyes slide off the page like a cheese off a cracker. I think my problem is that I just don't have the proper attention span--prose is easy to skim. You can't let your eyes wander down a poem and expect to feel the full effect. Therefore I didn't get a lot of the references that Baker makes to poets and their poetry. I mean I've heard the names--John Ashbery and Sarah Teasdale and Vachel Lindsay and Ezra Pound and so on--but I can't stop on a dime and recite their work. In fact, other than the work of Mother Goose I'm not sure I can recite any poem.

Chowder is an amiable companion. The irony of it all is that the slender novel is better than any introduction that Chowder could write. He's full of non sequiturs, my favorite being a chapter that begins, "God, I wish I was a canoe." He's also a needy, whiny kind of guy, obsessed with who gets published in the New Yorker, so much so that he makes their current poetry editor, Paul Muldoon, a character of sorts. Muldoon teaches at Princeton, and I see him around occasionally, so lines like these had amusing resonance: "He teaches at Princeton. He's probably there right now, talking to students. 'Hello, poetry students, I'm Mr. Paul Muldoon.'" Late in the book Chowder describes Muldoon being besieged in Switzerland. In a chat today on the New Yorker's web site, Muldoon confirms that is sometimes besieged, assailed, and once even stormed.

The book also cut pretty close to the bone. Chowder is in his fifties and realizes he is something of a disappointment. He is in debt and has no steady job. Although he is anthologizing a book of rhyming poems, he himself writes non-rhyming poems (he calls them "plums"). Someone asks him if he is putting together the book out of self-hatred and he agrees. When he tells a class that poetry is a young person's game he breaks into tears. As someone who is too close to fifty to contemplate and is not where I thought I'd be, the book got under my skin.

One of these days, when I have nothing but free time, I'm going to see if I can't sit down and read a book of poems. Chowder has all sorts of suggestions, most notably Mary Oliver.

Comments

Post a Comment