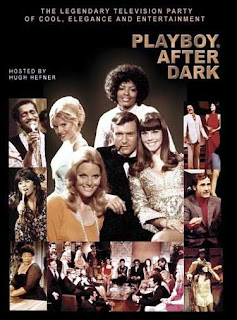

Playboy After Dark

Over the past week or two I've been watching DVDs of a curious artifact in the history of American TV: Playboy After Dark, a variety show that was hosted by Playboy magazine's publisher and editor Hugh Hefner. They are fascinating time capsules.

Over the past week or two I've been watching DVDs of a curious artifact in the history of American TV: Playboy After Dark, a variety show that was hosted by Playboy magazine's publisher and editor Hugh Hefner. They are fascinating time capsules.The show had two incarnations. In 1959-60 it ran for one year under the name Playboy's Penthouse. The DVD collection contains a long, self-congratulatory yet revealing interview with Hefner in which he talks about the genesis of the show. His desire was to be the personification of the ideal Playboy man, and thus he remade himself to fit that image. The show was a representation of a cocktail party at his bachelor pad, with beautiful girls strategically placed like furniture and young men in tuxedos, listening to jazz and talking about the issues of the day.

This seems quaint now, but there is a very appealing aspect to the show, especially since the period is somewhat in vogue now, due to Mad Men. The first volume of DVDs contain two shows from this period. One of them is dominated by the talent of Sammy Davis Jr., who performs in his inimitable style. Hefner mentions in the interview that the show was not carried on stations in Southern states, because the show had whites and blacks intermingling as equals. The other, in retrospect, packs quite a wallop, featuring Lenny Bruce, Ella Fitzgerald, and Nat King Cole (who doesn't sing). Since the show is set up as a party, Bruce does his thing sitting on a sofa, surrounded by listening guests. Author Rona Jaffe is also a guest, discussing her new book, and Hefner shows a clip from the movie that was made from it (he shows it from a projector onto a screen on the wall). My favorite part was when composer Cy Coleman (who wrote the theme of the show) performs his new song, which was just about to be recorded by Frank Sinatra--"The Best Is Yet to Come."

The attitudes of swells of the late fifties are on full display here, including a snooty attitude toward rock and roll (the Playboy man of that time dug jazz). But when the show returned ten years later, rock was embraced, as it was the time of psychedelia. The name was changed to Playboy After Dark, no doubt because the Penthouse name had been co-opted by Bob Guccione, and the show now reflected the times, looking a lot like Laugh-In--lots of kaleidoscope images, girls in miniskirts, and men in ruffled shirts and medallions.

The shows were mixtures of comedy and music, with the emphasis on the latter, and since different styles were straddled there were some interesting pairings. In one episode a barefoot Linda Ronstadt belted out some country tunes, and then later joined smooth-voiced jazz singer Billy Eckstine for a duet on "God Bless the Child." Joe Cocker and the Grease Band were another musical guest. On another show Sonny and Cher, Vic Damone, and Canned Heat were all guests, and played a game with Hef in which they described what animals they would be (Sonny, with Cher giving him a malevolent stare, said he would be a cat).

The comedy sequences don't hold up well. Mostly they are visits by established talk-show denizens such as Louis Nye, Dick Shawn, and Larry Storch, doing mild bits that didn't seem that funny even then. Sid Caesar does some voices, and Mort Sahl talks about the politics of sex. A nadir is when Rex Reed, flamboyant in a white suit, does some improv with Patty Duke.

As with the earlier show, one of the later episodes is dominated by Davis. He joins Anthony Newley for a medley, with Bill Cosby vamping behind them, and then is surprised by Jerry Lewis and Peter Lawford. The standard show-biz schmoozing commences, with Davis, referring to men as "cats" telling Hef how much Lewis means to him, and then joining him for a song.

These shows are pretty fascinating, not only for the talent involved but what they say about times gone by. I've been reading Playboy for thirty-five years and am not about to stop, but I recognize its weaknesses. The editorial board may support feminism, but they can't eradicate the essential sexism of the whole enterprise, which is magnified by these shows. The models are adornment, with blank stares on their faces. In the later years Barbi Benton was Hef's girlfriend, and she is like an appendage, staring up at him with an admiring gaze that suggests she's been drugged or hypnotized. This also represents a time when Playboy was much more relevant--in one show Hef shows off a model of the DC-9 the company had purchased. That plane was sold long ago, as the magazine's circulation dropped (and continues to drop). At one time they sold seven million copies a month, several times what they do now.

Have you seen the segment when George Carlin does standup on it? It was on YouTube a while back (deleted months ago) and it was quite fascinating to see. It was in the middle of his transformation from conventional to groundbreaking comedian; he'd grown the beard, but he actually still looked quite different from what most people knew him to look like from the early 1970s.

ReplyDeleteHis routine is mainly a segment from what would be his 'AM/FM' album, would've been quite cutting edge for a 1970 TV show.