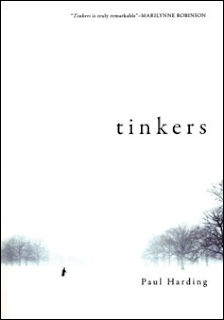

Tinkers

Tinkers, a novel by Paul Hardy, seemed to take everyone by surprise when it won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction last year. It wasn't highly reviewed or publicized, and Hardy is a first-time novelist. It tells the simple story of two men: a father and son.

Tinkers, a novel by Paul Hardy, seemed to take everyone by surprise when it won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction last year. It wasn't highly reviewed or publicized, and Hardy is a first-time novelist. It tells the simple story of two men: a father and son.Shifting narrative points of view, Hardy begins with George Crosby, who is a few days away from death in modern times. He seems to be an ordinary man, who had a passion for repairing clocks. He lives in northeastern Massachusetts, but grew up in Maine, the son of a tinker and salesman, who sold goods from a horse-drawn carriage through the backwoods in the 1920s (there's a lovely passage on Howard, the tinker's, interaction with an old hermit).

Howard was an epileptic, and when his wife brings home brochures from an asylum he decides to leave. This is told in between passages of George's gradual descent into death, with his extended family surrounding him.

A slim volume, Tinkers is short on plot but heavy, perhaps too heavy, on flights of literary fancy. There are some beautiful sections, and I loved a description of how Howard's brain felt after a fit: like "a jar full of rusty keys and old screws." But there are times the writing was so light and airy my eye just glided off the page.

The book also seems to take a very fatalistic view of life. Perhaps it can be summed up in this passage, while George, as a boy, is chopping wood: "Your cold mornings are filled with the heartache about the fact that although we are not at ease in this world, it is all we have, that it is ours but that it is full of strife, so that all we can call our own is strife; but even that is better than nothing at all, isn't it?"

Comments

Post a Comment