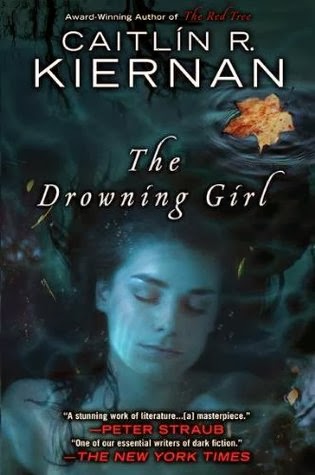

The Drowning Girl

"'I'm going to write a ghost story now,' she typed. 'A ghost story with a mermaid and a wolf,' she also typed. I also typed."

So begins Caitlin R. Kiernan's evocative novel The Drowning Girl, which starts the reader off balance by being told in both the first and third person at the same time. It deals with ghosts, mermaids, werewolves, sea monsters, Little Red Riding Hood, and the Black Dahlia murder case, among other touchstones.

The reader is in the thrall of India Morgan Phelps, or Imp for short, a woman whose mother and grandmother were both psychotic. India says, "It's a myth that crazy people don't know they're crazy. Many of us are surely as capable of epiphany and introspection as anyone else, maybe more so. I suspect we spend far more time thinking about our thoughts than do sane people."

India is fascinated with a painting by a New England artist called The Drowning Girl. It depicts a naked young woman, standing on the shore of body of water, seemingly startled by someone or something. India researches the painter, and learns that were was an incident at the river involving some unseen creature attacking a young girl.

Later, she is driving by the river at night when she spots a naked young woman standing by the side of the road. That is Eva Canning. To confuse us even further, there are possibly two Eva Cannings, and they might be mermaids. "Still, this is what I remember, that I met Eva Canning twice, once in July and again in November, and that both times were the first time we met."

I imagine this novel is catnip for a certain kind of reader, and I found it interesting in fits and starts. Narrating a book from the mind of someone who may be crazy, and is therefore unreliable, is a tough strategy, but Kiernan is successful most of the time, though I couldn't swear I knew what was going on. Also, relying on describing paintings (fictional paintings) which the reader can't see, but can only imagine, is also difficult, but this is also pulled off with aplomb.

The Drowning Girl defies usual criticism, though, because it is a challenge to the reader, a puzzle to be solved. As Imp puts it, perhaps speaking for the author, "My stories shape-shift like mermaids and werewolves. A lycanthropy of nouns, verbs, and adjectives, subjects and predicates, and so on and so forth."

So begins Caitlin R. Kiernan's evocative novel The Drowning Girl, which starts the reader off balance by being told in both the first and third person at the same time. It deals with ghosts, mermaids, werewolves, sea monsters, Little Red Riding Hood, and the Black Dahlia murder case, among other touchstones.

The reader is in the thrall of India Morgan Phelps, or Imp for short, a woman whose mother and grandmother were both psychotic. India says, "It's a myth that crazy people don't know they're crazy. Many of us are surely as capable of epiphany and introspection as anyone else, maybe more so. I suspect we spend far more time thinking about our thoughts than do sane people."

India is fascinated with a painting by a New England artist called The Drowning Girl. It depicts a naked young woman, standing on the shore of body of water, seemingly startled by someone or something. India researches the painter, and learns that were was an incident at the river involving some unseen creature attacking a young girl.

Later, she is driving by the river at night when she spots a naked young woman standing by the side of the road. That is Eva Canning. To confuse us even further, there are possibly two Eva Cannings, and they might be mermaids. "Still, this is what I remember, that I met Eva Canning twice, once in July and again in November, and that both times were the first time we met."

I imagine this novel is catnip for a certain kind of reader, and I found it interesting in fits and starts. Narrating a book from the mind of someone who may be crazy, and is therefore unreliable, is a tough strategy, but Kiernan is successful most of the time, though I couldn't swear I knew what was going on. Also, relying on describing paintings (fictional paintings) which the reader can't see, but can only imagine, is also difficult, but this is also pulled off with aplomb.

The Drowning Girl defies usual criticism, though, because it is a challenge to the reader, a puzzle to be solved. As Imp puts it, perhaps speaking for the author, "My stories shape-shift like mermaids and werewolves. A lycanthropy of nouns, verbs, and adjectives, subjects and predicates, and so on and so forth."

Comments

Post a Comment