The Wright Brothers

As school children we knew that the Wright Brothers invented the airplane. Some of us even knew details like Kitty Hawk, or that it happened in 1903. I toured their long-time home and bicycle shop (although they were no longer in Dayton, Ohio, but in Greenfield Village in my home town of Dearborn, Michigan). But I wonder if kids today know who the Wright Brothers were, or that in the space of one of the brother's lifetime, he would hear of a plane traveling faster than the speed of sound?

Popular historian David McCullough, who revived the reputations of John Adams and Harry Truman, has taken on the mild-mannered brothers who changed the face of transportation in The Wright Brothers. They make for a challenging subject, because while what they did was momentous, they weren't that particularly interesting. They and their younger sister, Katharine, who was much involved with their careers, seemed to have no other life than the airplane business. Wilbur and his younger brother Orville never married, and when Katharine did, at the age of 52, Orville felt betrayed (Wilbur was dead by then).

But what makes the story is the improbability of it. As McCullough writes: "From ancient times and into the Middle Ages, man had dreamed of taking to the sky, of soaring into the blue like the birds. One savant in Spain in the year 875 is known to have covered himself with feathers in the attempt. Others devised wings of their own design and jumped from rooftops and towers—some to their deaths—in Constantinople, Nuremberg, Perugia. Learned monks conceived schemes on paper. And starting about 1490, Leonardo da Vinci made the most serious studies. He felt predestined to study flight, he said, and related a childhood memory of a kite flying down onto his cradle."

By the late nineteenth century many were attempting to become the first to conquer the air. Hot air balloons were around, and many had built gliders that worked, but no one had managed to go aloft by engine power. But, "the most prominent engineers, scientists, and original thinkers of the nineteenth century had been working on the problem of controlled flight, including Sir George Cayley, Sir Hiram Maxim, inventor of the machine gun, Alexander Graham Bell, and Thomas Edison. None had succeeded. Hiram Maxim had reportedly spent $100,000 of his own money on a giant, steam-powered, pilotless flying machine only to see it crash in attempting to take off."

Therefore, "the fact that they had had no college education, no formal technical training, no experience working with anyone other than themselves, no friends in high places, no financial backers, no government subsidies, and little money of their own," makes the entire thing seem like fiction.

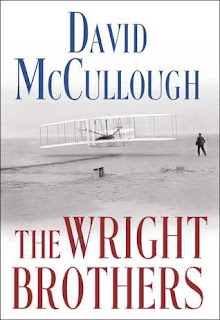

The brothers were always tinkerers. The sons of a bishop in Dayton, they opened a bicycle shop, but had always been fascinated by the prospect of flying. Over the course of a few years they traveled to the Outer Banks of North Carolina because of the wind, and on a December day in 1903 they accomplished what they set out to do. The photo of that flight is on the cover of the book, with Orville at the controls and Wilbur running alongside.

But the story doesn't end there. They would continue to experiment at a large field near Dayton, and then in France. The U.S. government wasn't much interested in their invention, but the French were. Wilbur stayed there for almost a year, stunning spectators with long flights. Orville survived a serious crash, but his passenger was killed, the first fatality in an airplane. The brothers became very rich and soon the possibilities of the airplane became apparent to everyone. Unfortunately, they also became war machines.

McCullough hits all the right notes, such as calling out the skeptics: "an article in the September issue of the popular McClure’s Magazine written by Simon Newcomb, a distinguished astronomer and professor at Johns Hopkins University, dismissed the dream of flight as no more than a myth. And were such a machine devised, he asked, what useful purpose could it possibly serve?" He also manages to stress, without hyperbole, that what the brothers did changed the face of history, and I think he likes that it was done by two straightforward, scandal-free men.

Wilbur died at 45 years old, and as previously stated, Orville died in 1948, long enough to see planes turned into delivers of atomic bombs and go faster than the speed of sound. McCullough appropriately ends the book: "On July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong, another American born and raised in western Ohio, stepped onto the moon, he carried with him, in tribute to the Wright brothers, a small swatch of the muslin from a wing of their 1903 Flyer."

Popular historian David McCullough, who revived the reputations of John Adams and Harry Truman, has taken on the mild-mannered brothers who changed the face of transportation in The Wright Brothers. They make for a challenging subject, because while what they did was momentous, they weren't that particularly interesting. They and their younger sister, Katharine, who was much involved with their careers, seemed to have no other life than the airplane business. Wilbur and his younger brother Orville never married, and when Katharine did, at the age of 52, Orville felt betrayed (Wilbur was dead by then).

But what makes the story is the improbability of it. As McCullough writes: "From ancient times and into the Middle Ages, man had dreamed of taking to the sky, of soaring into the blue like the birds. One savant in Spain in the year 875 is known to have covered himself with feathers in the attempt. Others devised wings of their own design and jumped from rooftops and towers—some to their deaths—in Constantinople, Nuremberg, Perugia. Learned monks conceived schemes on paper. And starting about 1490, Leonardo da Vinci made the most serious studies. He felt predestined to study flight, he said, and related a childhood memory of a kite flying down onto his cradle."

By the late nineteenth century many were attempting to become the first to conquer the air. Hot air balloons were around, and many had built gliders that worked, but no one had managed to go aloft by engine power. But, "the most prominent engineers, scientists, and original thinkers of the nineteenth century had been working on the problem of controlled flight, including Sir George Cayley, Sir Hiram Maxim, inventor of the machine gun, Alexander Graham Bell, and Thomas Edison. None had succeeded. Hiram Maxim had reportedly spent $100,000 of his own money on a giant, steam-powered, pilotless flying machine only to see it crash in attempting to take off."

Therefore, "the fact that they had had no college education, no formal technical training, no experience working with anyone other than themselves, no friends in high places, no financial backers, no government subsidies, and little money of their own," makes the entire thing seem like fiction.

The brothers were always tinkerers. The sons of a bishop in Dayton, they opened a bicycle shop, but had always been fascinated by the prospect of flying. Over the course of a few years they traveled to the Outer Banks of North Carolina because of the wind, and on a December day in 1903 they accomplished what they set out to do. The photo of that flight is on the cover of the book, with Orville at the controls and Wilbur running alongside.

But the story doesn't end there. They would continue to experiment at a large field near Dayton, and then in France. The U.S. government wasn't much interested in their invention, but the French were. Wilbur stayed there for almost a year, stunning spectators with long flights. Orville survived a serious crash, but his passenger was killed, the first fatality in an airplane. The brothers became very rich and soon the possibilities of the airplane became apparent to everyone. Unfortunately, they also became war machines.

McCullough hits all the right notes, such as calling out the skeptics: "an article in the September issue of the popular McClure’s Magazine written by Simon Newcomb, a distinguished astronomer and professor at Johns Hopkins University, dismissed the dream of flight as no more than a myth. And were such a machine devised, he asked, what useful purpose could it possibly serve?" He also manages to stress, without hyperbole, that what the brothers did changed the face of history, and I think he likes that it was done by two straightforward, scandal-free men.

Wilbur died at 45 years old, and as previously stated, Orville died in 1948, long enough to see planes turned into delivers of atomic bombs and go faster than the speed of sound. McCullough appropriately ends the book: "On July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong, another American born and raised in western Ohio, stepped onto the moon, he carried with him, in tribute to the Wright brothers, a small swatch of the muslin from a wing of their 1903 Flyer."

Comments

Post a Comment