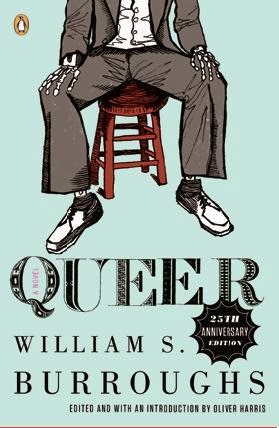

Queer

"When I lived in Mexico City at the end of the 1940s, it was a city of nine million people, with clear sparkling air and the sky that special shade of blue that goes so well with circling vultures, blood, and sand--the raw, menacing, pitiless Mexican blue." So writes William S. Burroughs in the 1985 introduction to Queer, his novel from the early '50s, which was not published for thirty years.

Today is Burroughs' 100th birthday. I've written about Naked Lunch, and I wanted to read something else by him for the occasion, and since I've also been reading about Mexico, this was a good choice, though it's not his first novel. In fact, this is something of a continuation of his first novel, Junky. The same character, Lee (based on himself--Jack Kerouac used the same name in his avatar for Burroughs in On the Road) is prowling around Mexico City, living off of G.I. benefits, hanging out in bars with other ex-pats.

The opening sentence of the book is "Lee turned his attention to a Jewish boy named Carl Steinberg he had known casually for about a year. The first time he saw Carl, Lee thought, 'I could use that, if the family jewels weren't in pawn to Uncle Junk.'"

It's no wonder why this book couldn't be published in the U.S.--it is explicitly about homosexuality and drugs. Burroughs has never been considered a "gay writer," perhaps because his alter-ego in this book is what might be consider a stereotypical self-hating homosexual. But it wasn't the time for a book like this. As Oliver Harris points out in the introduction, "This was not only the era of McCarthyism and the Korean War but the lavender scare, the Homintern conspiracy, and the demonization of homosexuality as un-American, viral contagion and threat to the health of the body politic."

The plot of the book, such as it, has Lee obsessed with a young American named Gene Allerton. Allerton is straight, but succumbs to Lee's patronage, and though repulsed by his advances, consents to sleep with him occasionally. He and Lee take a trip to South America, searching for a drug called Yage. Later, Lee will return to Mexico City, wondering what happened to his great love.

What I love about the Beats, including Burroughs, is their wonderful sense of humor and language. There are laugh out loud lines here, like "'I hear they are purging the State Department of queers. If they do, they will be operating with a skeleton staff,'" or "'Sit down on your ass, or what's left of it after four years in the navy.'" But he can also set a scene magically: "Lee was sitting with Winston Moor in the Rathskeller, drinking double tequilas. Cuckoo clocks and moth-eaten deer heads gave the Rathskeller a dreary, out-of-place, Tyrolean look. A smell of spilt beer, overflowing toilets, and sour garbage hung in the place like a thick fog and drifted out into the street through narrow, inconvenient swinging doors. A television set was out of order half the time and emitted horrible, guttural squawks like a Frankenstein monster."

I particularly loved a passage when Lee, feeling sorry for himself, spins tale of chess masters at the bar: "'Did you ever have the good fortune to see the Italian master Tetrazzini perform?' Lee lit Mary's cigarette. 'I say 'perform' advisedly, because he was a great showman and, like all showmen, not above charlatanism and at times downright trickery. Sometimes he used smoke screens to hide his maneuvers from the opposition--I mean literal smoke screens, of course. He a had a corps of trained idiots who would rush in a given signal and eat all the pieces. With defeat staring him in the face--as it often did, because actually he knew nothing of chess but the rules and wasn't too sure of those--he would leap up yelling, 'You cheap bastard! I saw you palm that queen!' and ram a broken teacup into the opponent's face. In 1922 he was rid out of Prague on a rail. The next time I saw Tetrazzini was in the Upper Ubangi. A complete wreck. Peddling unlicensed condoms. That was the year of the rinderpast, when everything died, even the hyenas."

Though the book is very funny, it's overall tone is melancholy. Burroughs writes that Junky was about a man who took power from his addiction, while Queer was a man disintegrated about it. There is also this plaintive line from the introduction (Burrough's accidentally killed his wife in a game of William Tell): "I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan's death, and to a realization of the extent to which this event has motivated and formulated my writing."

Today is Burroughs' 100th birthday. I've written about Naked Lunch, and I wanted to read something else by him for the occasion, and since I've also been reading about Mexico, this was a good choice, though it's not his first novel. In fact, this is something of a continuation of his first novel, Junky. The same character, Lee (based on himself--Jack Kerouac used the same name in his avatar for Burroughs in On the Road) is prowling around Mexico City, living off of G.I. benefits, hanging out in bars with other ex-pats.

The opening sentence of the book is "Lee turned his attention to a Jewish boy named Carl Steinberg he had known casually for about a year. The first time he saw Carl, Lee thought, 'I could use that, if the family jewels weren't in pawn to Uncle Junk.'"

It's no wonder why this book couldn't be published in the U.S.--it is explicitly about homosexuality and drugs. Burroughs has never been considered a "gay writer," perhaps because his alter-ego in this book is what might be consider a stereotypical self-hating homosexual. But it wasn't the time for a book like this. As Oliver Harris points out in the introduction, "This was not only the era of McCarthyism and the Korean War but the lavender scare, the Homintern conspiracy, and the demonization of homosexuality as un-American, viral contagion and threat to the health of the body politic."

The plot of the book, such as it, has Lee obsessed with a young American named Gene Allerton. Allerton is straight, but succumbs to Lee's patronage, and though repulsed by his advances, consents to sleep with him occasionally. He and Lee take a trip to South America, searching for a drug called Yage. Later, Lee will return to Mexico City, wondering what happened to his great love.

What I love about the Beats, including Burroughs, is their wonderful sense of humor and language. There are laugh out loud lines here, like "'I hear they are purging the State Department of queers. If they do, they will be operating with a skeleton staff,'" or "'Sit down on your ass, or what's left of it after four years in the navy.'" But he can also set a scene magically: "Lee was sitting with Winston Moor in the Rathskeller, drinking double tequilas. Cuckoo clocks and moth-eaten deer heads gave the Rathskeller a dreary, out-of-place, Tyrolean look. A smell of spilt beer, overflowing toilets, and sour garbage hung in the place like a thick fog and drifted out into the street through narrow, inconvenient swinging doors. A television set was out of order half the time and emitted horrible, guttural squawks like a Frankenstein monster."

I particularly loved a passage when Lee, feeling sorry for himself, spins tale of chess masters at the bar: "'Did you ever have the good fortune to see the Italian master Tetrazzini perform?' Lee lit Mary's cigarette. 'I say 'perform' advisedly, because he was a great showman and, like all showmen, not above charlatanism and at times downright trickery. Sometimes he used smoke screens to hide his maneuvers from the opposition--I mean literal smoke screens, of course. He a had a corps of trained idiots who would rush in a given signal and eat all the pieces. With defeat staring him in the face--as it often did, because actually he knew nothing of chess but the rules and wasn't too sure of those--he would leap up yelling, 'You cheap bastard! I saw you palm that queen!' and ram a broken teacup into the opponent's face. In 1922 he was rid out of Prague on a rail. The next time I saw Tetrazzini was in the Upper Ubangi. A complete wreck. Peddling unlicensed condoms. That was the year of the rinderpast, when everything died, even the hyenas."

Though the book is very funny, it's overall tone is melancholy. Burroughs writes that Junky was about a man who took power from his addiction, while Queer was a man disintegrated about it. There is also this plaintive line from the introduction (Burrough's accidentally killed his wife in a game of William Tell): "I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan's death, and to a realization of the extent to which this event has motivated and formulated my writing."

Comments

Post a Comment