Woodstock

I thought I would miss the fiftieth anniversary of Woodstock, as I've already written about the festival here, when I visited the site of the festival ten years ago. But the radio was full of Woodstock. One station in Philadelphia played the concert exactly as it happened, including weather delays and stage announcements. I got Woodstock fever.

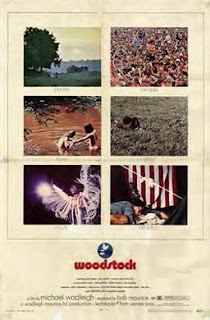

It occurred to me I had never seen the film of the concert, at least not all the way through. It streams on several platforms, so I rented it and watched the 1994 "director's cut," which is almost four hours long. It flew by.

Directed by Michael Wadleigh, with able assistance from a team of editors (that included Martin Scorsese), Woodstock is considered one of the best documentaries ever made. It won the Oscar for that category in 1970, I think the only concert movie to do so. Of course it is more than a concert movie--the strength of the film is that it makes us feel like we were there.

The film begins at the beginning, with the construction of the stage, and ends at the ending, with the trash being picked up. Although the music acts aren't played in strict chronological order, they do hew to Richie Havens opening and Jimi Hendrix closing. In between are several musicians, although many big groups are left on the cutting room floor: The Grateful Dead, The Band, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Blood, Sweat, and Tears.

In between the musical numbers are interstitial segments on the festival attendees, grouped in thematic sets. We get a young couple talking about free love, a segment showing young people lined up at pay phones to call home, images of babies and toddlers who were there (usually naked), and nudity by adults, skinny-dipping in the nearby lake. These are like postcards from the past, time frozen, and it's hard to reconcile that these people are now pushing seventy at their youngest. A teenager today might watch and have a moment of recognition: "Grandma?"

There are also segments on the ugly parts of the festival. The mud, the traffic jams, the lack of food, water, and adequate sanitation, and the medical issues. The army actually flew in help for the latter. Two people died at Woodstock, but then again, two babies were born, so the cosmic balance remained intact. Not everyone had a good time--one young lady is shown bursting into tears, wanting to go home, because "it's too crowded."

It was crowded, with an estimated 400,000 attending. There are many shots of the crowd literally disappearing into the horizon. The last shot of the film is from a helicopter, over a sea of people. But many of these people didn't pay their way in. We see them climbing over the fence, and it becomes apparent that to the promoters that it is a free concert. A reporter questions promoter Artie Kornfeld, who admits that it is a financial disaster. In a split screen (which Wadleigh uses often), Kornfeld's talk of dollars and cents is contrasted with a pair cavorting nude in the tall grass.

But it's all about the music, man. We get The Who, Sly And The Family Stone, Janis Joplin, Ten Years After, Jefferson Airplane, and Crosby, Still, and Nash (in only their second gig). I think the three biggest highlights are Joan Baez, alone in the dark night, singing the old union song "Joe Hill" (after talking about her husband's arrest for draft evasion); Joe Cocker, wearing a tie-dyed shirt and playing air guitar while he sings "With A Little Help From My Friends," better even then The Beatles did, and Santana doing "Soul Sacrifice," highlighted by the electrifying drumming of Michael Shrieve.

Woodstock was nominated for an Oscar for Best Editing, and it's easy to see why. Again, the film often employs split screens, sometimes in diptych, sometimes in triptych. We may see three different images of Roger Daltrey, his bare chest gleaming, hands raised high, or three different shots of Alvin Lee's face as he plays "Going Home," but other times there are contrasted images, music played as we watch those in the audience. Everything seems to be laid out so carefully, and not an image is wasted.

There are so many great moments, especially the stage announcements, by Chip Monck, who was the lighting designer that got pressed into MC duty. He warns people about the brown acid. When the thunderstorm hits, he asks people to get away from the towers. He asks a young woman to go to the information booth because her boyfriend wants to ask her to marry him.

Hendrix closed the show on Monday morning, with only about a tenth of the audience remaining, but he ended it with a bang, segueing from "Voodoo Child" to "The Star-Spangled Banner" to "Purple Haze," and during that last song we see the acres of refuse, and a few stragglers, such as one man, with crutches, eating a watermelon.

The owner of the farm where the festival took place, Max Yasgur, spoke to the audience and congratulated them. Woodstock really became famous not only for the once-in-a-lifetime assemblage of musicians, but because that many young people, many of them on drugs, existed together in such harmony. There were no major disturbances. Some of the townspeople weren't happy--one man rails against them because "they're all on pot," but most, including the chief of police, are pleasantly surprised by the good behavior.

Woodstock is a document of the apotheosis of the counterculture of the '60s, but also a movie about the power of youth. This may be something that can not be recaptured, as Woodstock 1999 saw fire and destruction. Today a similar festival might find everyone looking at their phones. But despite the mud and the drugs and the lack of food, something special happened on those three days in New York, and the film captures it.

It occurred to me I had never seen the film of the concert, at least not all the way through. It streams on several platforms, so I rented it and watched the 1994 "director's cut," which is almost four hours long. It flew by.

Directed by Michael Wadleigh, with able assistance from a team of editors (that included Martin Scorsese), Woodstock is considered one of the best documentaries ever made. It won the Oscar for that category in 1970, I think the only concert movie to do so. Of course it is more than a concert movie--the strength of the film is that it makes us feel like we were there.

The film begins at the beginning, with the construction of the stage, and ends at the ending, with the trash being picked up. Although the music acts aren't played in strict chronological order, they do hew to Richie Havens opening and Jimi Hendrix closing. In between are several musicians, although many big groups are left on the cutting room floor: The Grateful Dead, The Band, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Blood, Sweat, and Tears.

In between the musical numbers are interstitial segments on the festival attendees, grouped in thematic sets. We get a young couple talking about free love, a segment showing young people lined up at pay phones to call home, images of babies and toddlers who were there (usually naked), and nudity by adults, skinny-dipping in the nearby lake. These are like postcards from the past, time frozen, and it's hard to reconcile that these people are now pushing seventy at their youngest. A teenager today might watch and have a moment of recognition: "Grandma?"

There are also segments on the ugly parts of the festival. The mud, the traffic jams, the lack of food, water, and adequate sanitation, and the medical issues. The army actually flew in help for the latter. Two people died at Woodstock, but then again, two babies were born, so the cosmic balance remained intact. Not everyone had a good time--one young lady is shown bursting into tears, wanting to go home, because "it's too crowded."

It was crowded, with an estimated 400,000 attending. There are many shots of the crowd literally disappearing into the horizon. The last shot of the film is from a helicopter, over a sea of people. But many of these people didn't pay their way in. We see them climbing over the fence, and it becomes apparent that to the promoters that it is a free concert. A reporter questions promoter Artie Kornfeld, who admits that it is a financial disaster. In a split screen (which Wadleigh uses often), Kornfeld's talk of dollars and cents is contrasted with a pair cavorting nude in the tall grass.

But it's all about the music, man. We get The Who, Sly And The Family Stone, Janis Joplin, Ten Years After, Jefferson Airplane, and Crosby, Still, and Nash (in only their second gig). I think the three biggest highlights are Joan Baez, alone in the dark night, singing the old union song "Joe Hill" (after talking about her husband's arrest for draft evasion); Joe Cocker, wearing a tie-dyed shirt and playing air guitar while he sings "With A Little Help From My Friends," better even then The Beatles did, and Santana doing "Soul Sacrifice," highlighted by the electrifying drumming of Michael Shrieve.

Woodstock was nominated for an Oscar for Best Editing, and it's easy to see why. Again, the film often employs split screens, sometimes in diptych, sometimes in triptych. We may see three different images of Roger Daltrey, his bare chest gleaming, hands raised high, or three different shots of Alvin Lee's face as he plays "Going Home," but other times there are contrasted images, music played as we watch those in the audience. Everything seems to be laid out so carefully, and not an image is wasted.

There are so many great moments, especially the stage announcements, by Chip Monck, who was the lighting designer that got pressed into MC duty. He warns people about the brown acid. When the thunderstorm hits, he asks people to get away from the towers. He asks a young woman to go to the information booth because her boyfriend wants to ask her to marry him.

Hendrix closed the show on Monday morning, with only about a tenth of the audience remaining, but he ended it with a bang, segueing from "Voodoo Child" to "The Star-Spangled Banner" to "Purple Haze," and during that last song we see the acres of refuse, and a few stragglers, such as one man, with crutches, eating a watermelon.

The owner of the farm where the festival took place, Max Yasgur, spoke to the audience and congratulated them. Woodstock really became famous not only for the once-in-a-lifetime assemblage of musicians, but because that many young people, many of them on drugs, existed together in such harmony. There were no major disturbances. Some of the townspeople weren't happy--one man rails against them because "they're all on pot," but most, including the chief of police, are pleasantly surprised by the good behavior.

Woodstock is a document of the apotheosis of the counterculture of the '60s, but also a movie about the power of youth. This may be something that can not be recaptured, as Woodstock 1999 saw fire and destruction. Today a similar festival might find everyone looking at their phones. But despite the mud and the drugs and the lack of food, something special happened on those three days in New York, and the film captures it.

Comments

Post a Comment